Bings, Bings are Wonderful Things

Exploring Hopetoun oil works bing

Hopetoun oil works, during demolition c.1952, with the bing in the background.

Hutches of spent shale being hauled by cable to the top of the bing. This view is thought to be Deans oil works.

F20012, first published 22nd March 2020

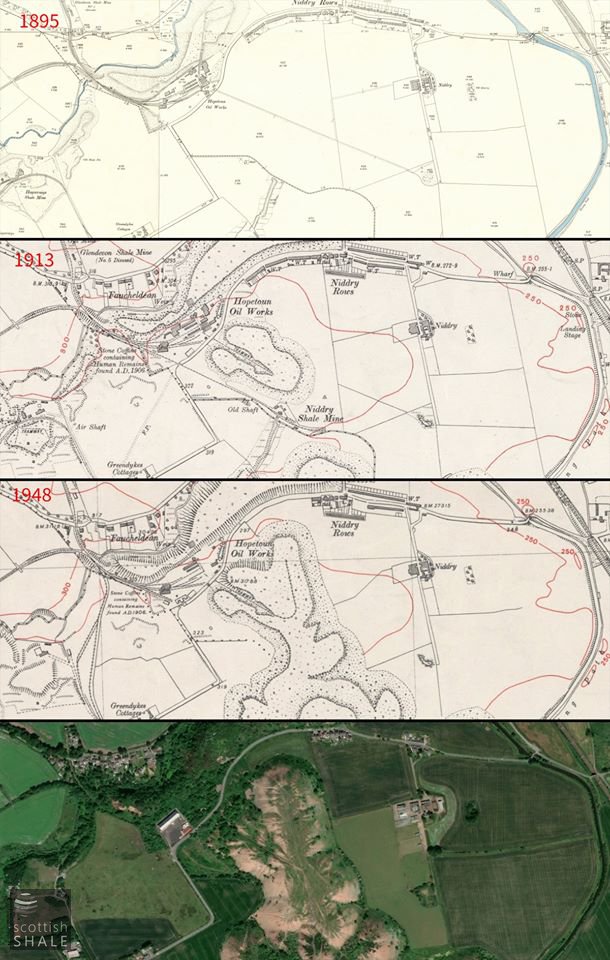

Big orange heaps of spent shale waste were once a distinctive feature of the West Lothian landscape, and two are now protected as scheduled monuments in recognition of their importance to Scotland's heritage. The scheduled “Greendykes bing” occupies much of the land between Broxburn and Winchburgh, and has a complicated outline of lobes and spurs resulting from waste tipped from two different oil works over various periods of history.

Broxburn's Albyn oilworks on the banks of the Union Canal was active from the late 1860's through to the mid 1920's. It first threw up bings of waste to the east and west of the works before building a mountain of spent shale that extended progressively northwards. On the lands of Niddry farm, more than half a mile to the north west, the rival Uphall oil company set up their Hopetoun oil works in 1872. Hopetoun's waste was first tipped to the north of the works, until the Faucheldean burn prevented further expansion. The works (by then owned by Young's company) were reconstructed in 1906, and a tramway formed beneath the main road to allow waste to be tipped on land to the south. This “Hopetoun South” bing was quickly extended southward and then dog-legged back on itself to fill the land behind the Niddry Rows. The residents of the rows, mostly oil workers at the Hopetoun oil works, increasing found themselves living in a dusty canyon between the old north (Faucheldean) bing and the still growing south bing.

For a while extension of the bing southwards was inhibited by the presence of No.44 “Niddry” shale mine. After this closed in 1916, and once all operations were under the ownership of Scottish Oils Ltd, opportunity was taken to progress the tipping southwards to meet Broxburn bing, forming the long plateau that exists today.

The spent shale that forms the bings is the material left once shale was heated to release oil, and might account for 80% of the original volume. This waste was loaded into tramway hutches (wagons) and hauled by cable up a steep incline. At the level top of the bing (or at intermediate platforms) hutches were pushed or hauled along temporary tramways to the tipping points. These tipping points were often arranged fan-line along an arc, creating the lobed profile still apparent today. At each tipping point, a chain was thrown through the spokes of the hutch wheel, and the hutch manfully lifted at one end to tip the contents over the precipice. Truly a job for heroes. The spent shale was a dusty grey colour when first tipped, and it is only with the passage of time that it has mellowed and rusted to form the characteristic orange-pink colour.

This colour is particularly apparent (and has a certain beauty) on the side of the Hopetoun south bing that faces the Greendykes road where vegetation is kept at bay, and fresh surfaces exposed, by the regular daredevil antics of trail bikes. The course of the old haulage incline from Hopetoun oil works to the top of the bing now provides the main route for trail bikes to ascend to the plateau This constant traffic loosens the ground and enables rain to wash down material creating ever deeper gullies.

Hopetoun Estates, owners of the land from long before the advent of the shale oil industry, do everything possible to deter the illegal trail-biking, but it's something that seems impossible to effectively police. Many would say that the biker's actions are causing irrecoverable damage to this national monument. There is also concern that the tracks of so many tyres do terrible damage to a special ecosystem of unusual plants that have become established since the last hutch was tipped in the 1940's, Many are committed to safeguarding the natural progression of nature that will gradually green the bings. There is an alternative view that the bings provide a vital leisure resource where youngsters can burn off energies and hone skills, and where future motor sport champions are nurtured. Some would maintain that they had a right to enjoy the man-made mountains that their great-grandparents laboured so hard to create.