A Bridge in Broxburn

Bridge 28 and the Stewartfield mines

Looking east towards bridge 28, with bings to the left and industrial buildings on the site of Albyn oil works.

Bridge 28 - still pleasantly oil-blackened.

F18017, first published 8th April 2018

No. 28 shows the same fine Georgian craftsmanship as other original bridges built for the opening of the Union Canal in the 1820's, however its parapet walls are of a coarser and more recent stonework, with evidence of many repairs and alterations through the years. Beside the bridge, crumbling abutment walls of yellow fireclay brick suggest that other bridges once spanned the canal at this point.

When first built, the bridge served a few rural fields, and will have carried little traffic. In the early 1860's however, Broxburn became the first centre of Scotland's new shale oil industry, marked by a proliferation of small-scale and short-lived oil works whose precise histories and locations are now uncertain. Most were built on canal-side sites for easy shipping of products. The largest and most persistent of these early works were to the north of the canal adjacent to bridge 28, and in 1878 this site was redeveloped as the Broxburn Oil Company's mighty new Albyn crude oil works.

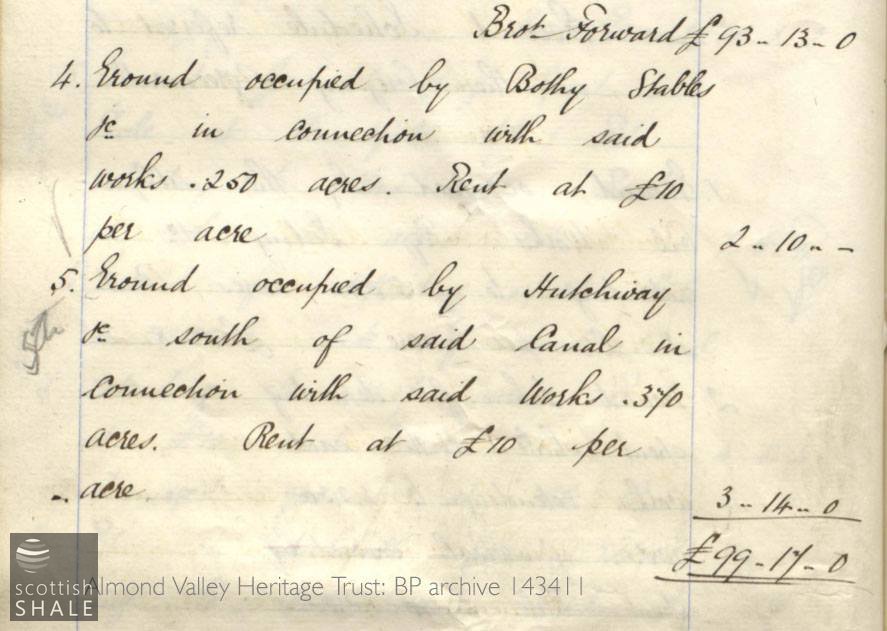

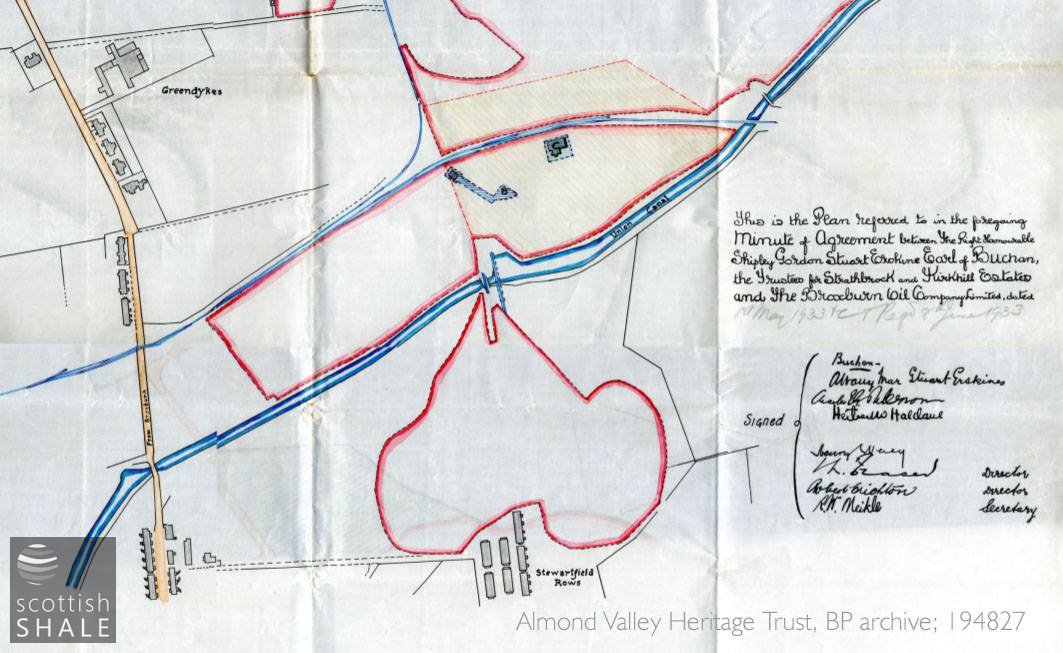

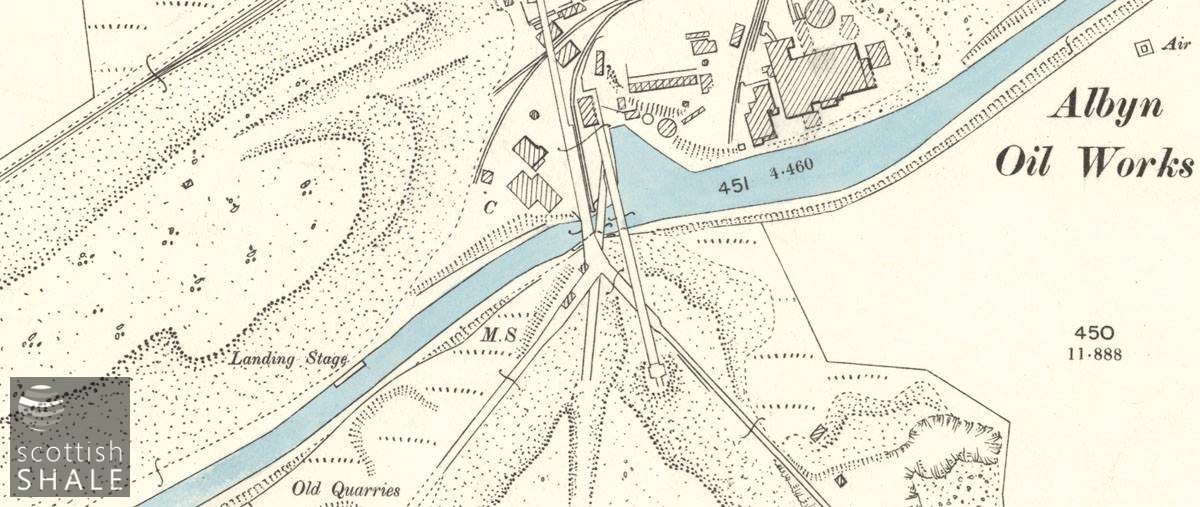

The 1895 OS map shows the Albyn works as a bewildering industrial network of buildings, plant and railways. Various hutchways converge to cross the canal at bridge 28, with the map suggesting a complicated multi-level arrangement of timber trestles, on which bogies hauled by continuously moving cables would deliver their loads to various destinations. To the south of the canal, Stewartfield No.1 and No.2 mines worked the steeply inclined seams of shale that lay beneath Broxburn town. Their output was transported north by hutchway over the canal to the breakers and retorts of Albyn oil works. Other bridges and gantries crossed the canal to carry waste south to be tipped in Stewartfield.

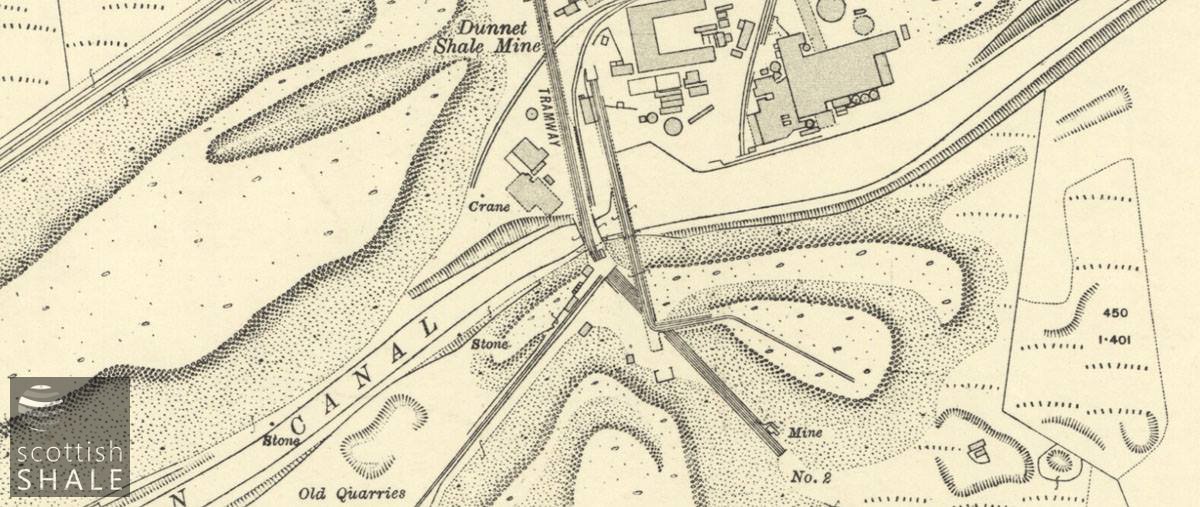

The layout of the Albyn works, and the arrangement of hutchways, continually evolved. By the early 20th century most land available to tip spent shale to the west, north and east of the works was exhausted and waste from the retorts were hauled south across the canal to be dumped in Stewartfield. This Stewartfield bing eventually threatened to engulf worker's housing at Stewartfield Rows, and the local weans often entertained themselves by rolling lumps down the bing and hitting the doors and windows of the cottages.

The Albyn works closed in 1926, the Stewartfield mines having closed a few years previously. Buildings and hutchways were gradually dismantled, but a landscape of industrial dereliction was left behind.

During the 1930's a steam navvy was let loose on Stewartfield bing to quarry blaes for the construction of the new Edinburgh to Glasgow trunk road, but this seems to have made little impression. It was not until the early 1970's that the bulk of Stewartfield bing was removed and the area landscaped, opening as Stewartfield playing fields and park in 1982.

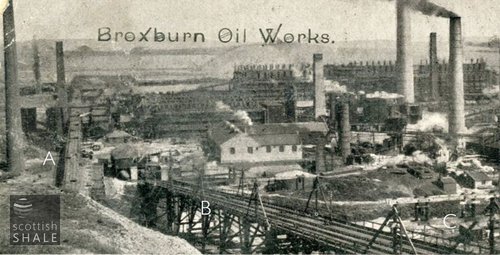

Above right: Section of a fuzzy printed postcard, with view taken from Stewartfield bing looking north towards the Albyn works. A indicates the haulage taking shale from the Stewartfield mines to the breaker, B is the haulage conveying spent shale to the bing, while C marks the banks of the canal which pass beneath these hutchways.

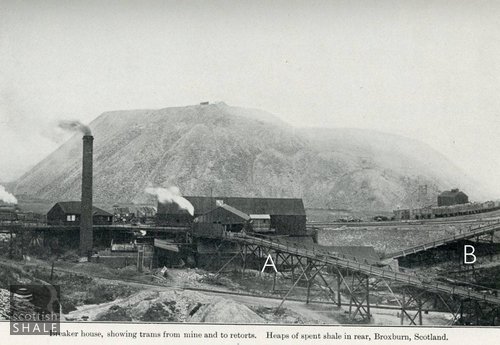

Above left: The shale breaker on the north side of the canal. A is the trestle and hutchway bringing shale from Stewartfield. B is the haulage taking the broken shale to load into the top of the retorts.

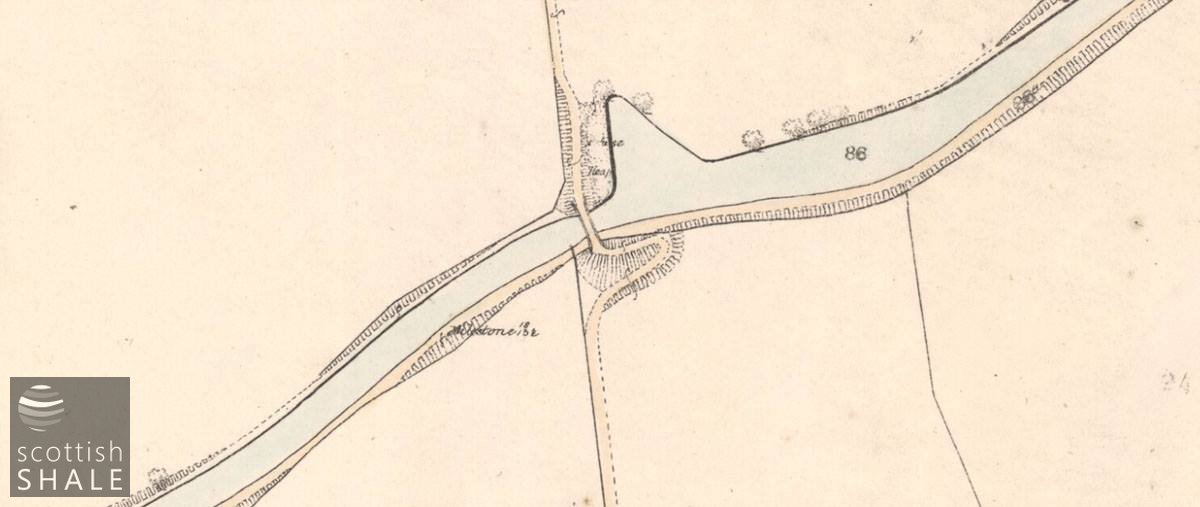

Open countryside in 1854

25" OS map image courtesy National Libraries of Scotland.

The scene in 1895, with at least three crossings of the canal. 25" OS map image courtesy National Libraries of Scotland.

The area in 1916, with haulage across the canal dumping spent shale on Stewartfield. 25" OS map image courtesy National Libraries of Scotland.

Modern aerial view.

Path south from the bridge, leading to Stewartfield playing fields.

The route northward to the Albyn oil works site remains blocked.

Former bridge abutment in undergrowth on the north side of the canal.

Former bridge abutment? on the southern side of the canal.

Rather rough and ready brickwork.