The Canal Builders and Broxburn's First Railways

East Mains Quarry and the Broxburn Railway

F22007, first published, 17th April 2022

In its brief heyday, the Union Canal formed the backbone of local industry and trade. Until railways stole the traffic, much of the coal, stone and other heavy products of West Lothian found their way to the markets of Edinburgh by boat. The canal was a massive piece of civil engineering, consuming huge quantities of dressed stone in the construction of aqueducts and bridges. Naturally the canal-builders sought sources of this stone that were close at hand, and developed a small quarry on the lands of East Mains, just to the west of Broxburn, where a 27 ft seam of “fine white and yellow liver rock” occurred close to the surface. Blocks of this sandstone needed only to be carted a short distance to the banks of the canal from where, (it might be imagined), these were shipped along the partially completed canal to where the mighty Almond aqueduct was being constructed.

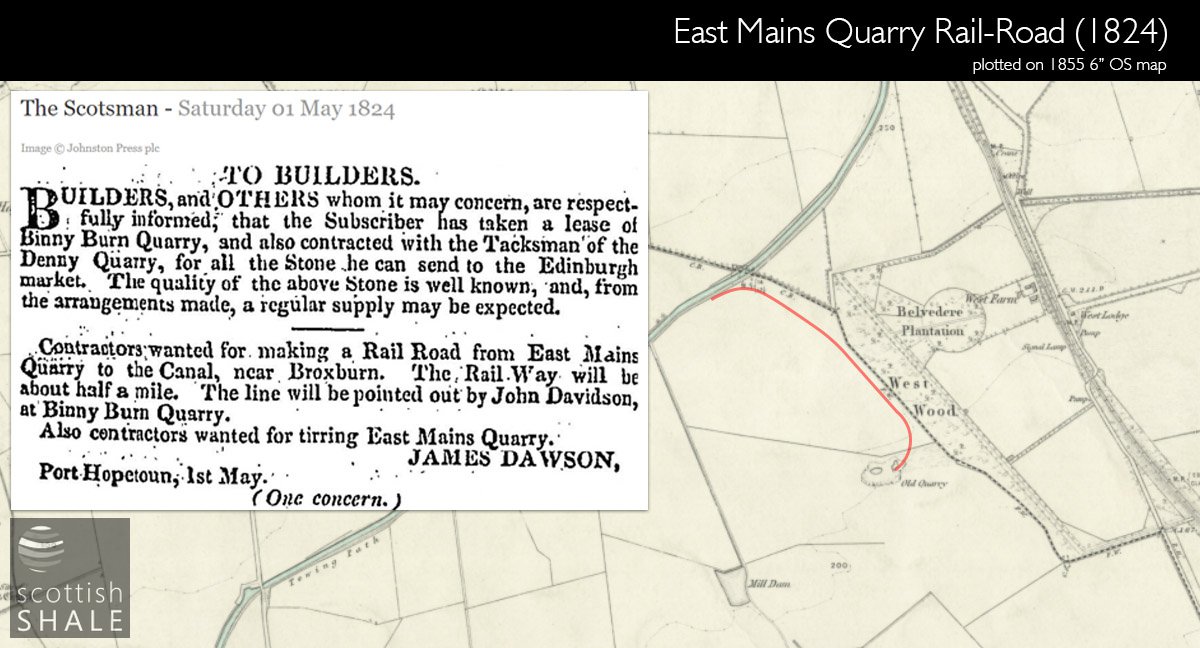

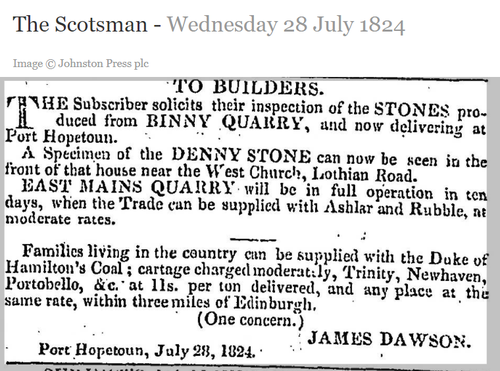

In 1821, once the canal was substantially complete, the quarry was put up for lease and production resumed in 1824. Newspaper adverts that appeared in 1824 outlined the intention to build a short rail-way to link the quarry to the Union canal, a third of a mile to the North. In all likelihood this would have been a simple horse-drawn tramway formed from cast-iron plates. Assuming that this was actually built, it may have been the first railway in the eastern parts of the county. It appears that the quarry was soon abandoned as the 1855 Ordnance Survey map shows only a small pit marked “old quarry” and no trace of any route between this and the canal.

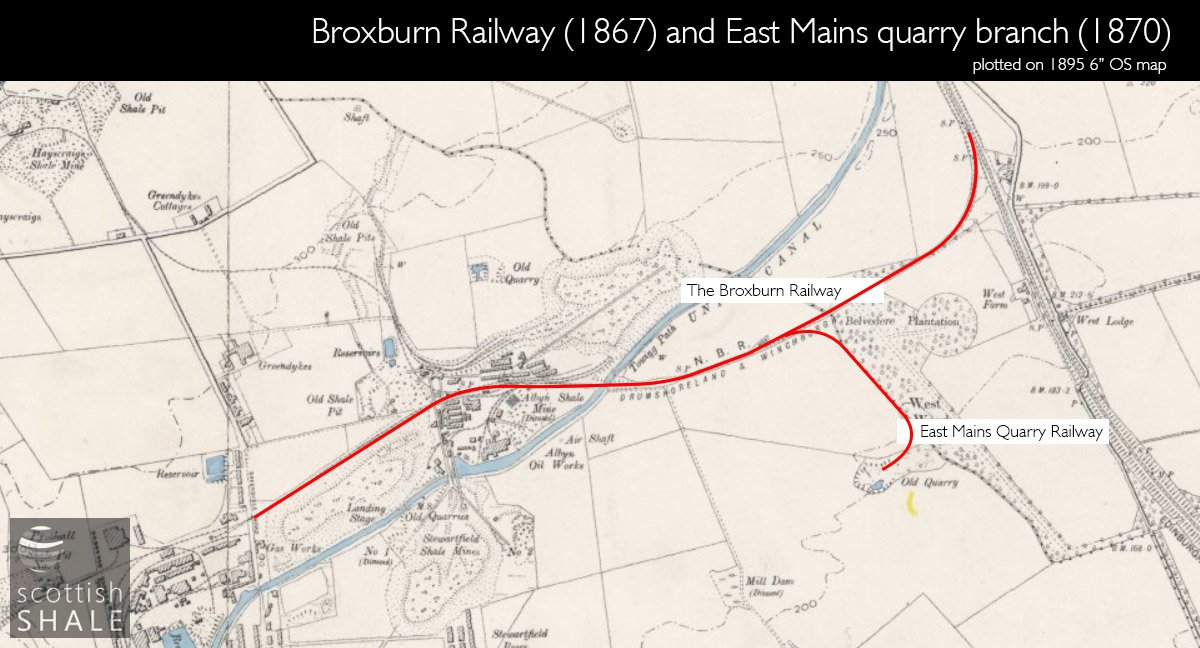

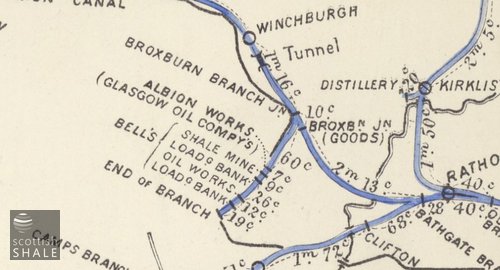

Both the main Edinburgh to Glasgow railway via Linlithgow, and the Edinburgh to Bathgate line, were built before the value of Broxburn's oilshale reserves was recognised. In 1859, Wishaw coalmaster Robert Bell leased the minerals of the Earl of Buchan's Broxburn estate. He was first to recognise the commercial value of oilshale and during the early 1860's drew up agreements with various entrepreneurs and investors who set up various oil works and refineries clustered around the Union Canal in Broxburn. Some oils were shipped out by canal, and a few “tank-boats” were specially constructed to transport crude oil to refineries in other parts of Scotland. The bulk of the output however seems to have been carted through the streets of Broxburn to reach the distant “Broxburn station” near Drumshoreland on the Edinburgh and Bathgate Railway. Robert Bell and others oil-masters were forced to pay the parish substantial sums to continually repair the cut-up road surface. Obviously Broxburn needed a railway, and it seems probable that Bell and his associates were behind the promotion of the the Broxburn Railway Company, which was authorised by an Act of Parliament in 1867.

The one and a half mile long railway left the E&G main line a little to the north of the Almond viaduct near Broomhouse farm, and headed west in a shallow cutting through the lands of Newliston house. Crossing the parish boundary into the Earl of Buchan's lands, the route continued discretely hidden in a cutting before emerging to cross the canal by a bridge, continuing on the northern side, terminating beside Greendykes Road, in the centre of Broxburn's oil works district.

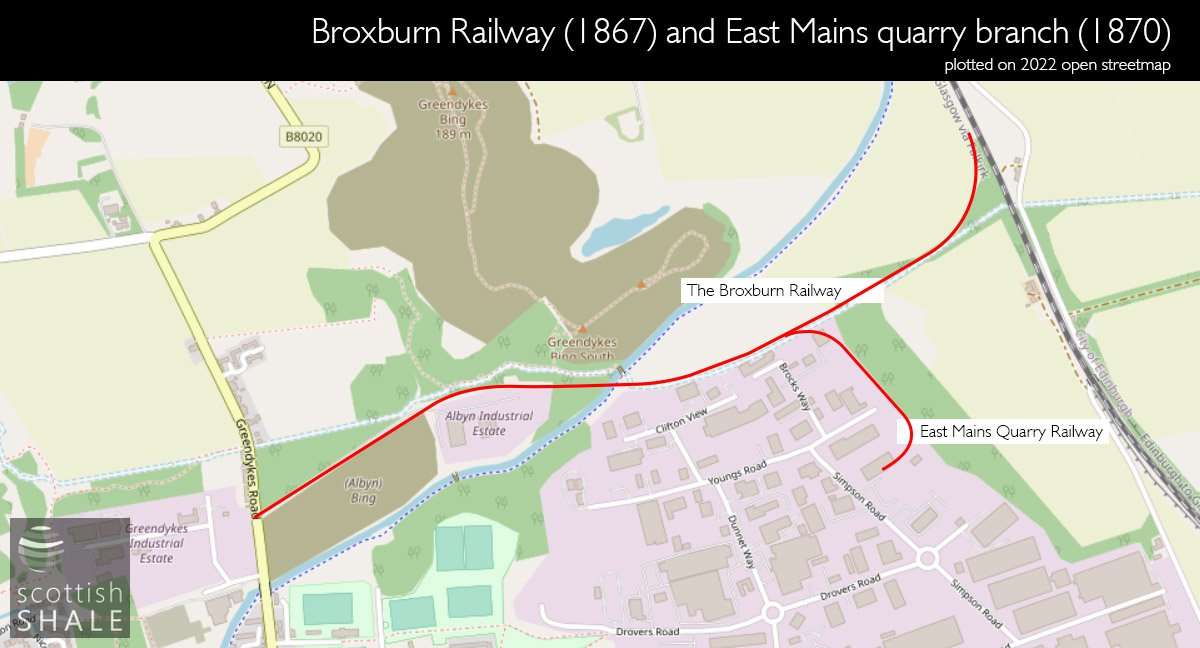

From the outset it was intended that traffic on the railway would be worked by the North British Railway, and in 1872 the NBR took ownership of the line. In the same year the NBR sought parliamentary powers to continue the line across Greendykes Road, looping south via Holygate to link to the Edinburgh and Bathgate line. It was a number of years before this was built however, and seems never formed a through route for main line trains. Only the Broxburn oil company's own pugs being permitted to infuriate road users by shunting to and fro across the level crossing on Greendykes Road.

A recently discovered bundle of papers revealed that the ever-enterprising Robert Bell reopened East Mains sandstone quarry, and on 5th August 1874 opened a new branch linking the quarry to the NBR Broxburn branch. This followed a course parallel to the woodland strip that marked the parish boundary, probably on the same route as the earlier quarry rail-way. The line was worked by a stationary engine that hauled wagons from the quarry by a rope, leaving them in an exchange siding from which they would be collected by an NBR engine. Operations seems to have been short lived as the 1895 OS map shows only an “old quarry” and shows no evidence of the quarry branch line ever existed. Presumably there was a further phase of working as the “old quarry” shown on the 1916 map was substantially bigger than the “old quarry” shown in 1895.

The Broxburn branch outlived the shale oil industry and was not closed by British Railways until about 1968. Much of the route can still be traced. At its eastern end, the line passes through part of the landscaped grounds of Newliston House that was cut-off and abandoned when the Edinburgh and Glasgow was built in the 1840's. Parts of this ornamental landscape are still evident. The line follows a wooded strip, giving views towards the Belvedere; a circular walled plantation that which must once have been a feature of a beautiful view from Newliston House. It then passes through the West Wood that marked the boundary of the estate, and boundary between the parishes of Kirkliston and Uphall. To the west, the line now forms the northern boundary of East Mains Industrial Estate. Rubbish is being dumped in the shallow cutting, the surrounding land has gone to waste and is now a playground for trail bikers. The railway bridge across canal disappeared some time around 2000 (if I remember correctly), but the route on the north side survives as roads and tracks serving the ramshackle group of industrial buildings that currently occupy the site of Albyn crude oil works.

All traces of the quarry and its railway now lie buried beneath the sheds and yards of East Mains Industrial Estate. The “fine white and yellow liver rock” once worked there can however still be admired in the monumental aqueducts and bridges of the Union Canal.