The Electric Ghosts of Hawk Hill Plantation

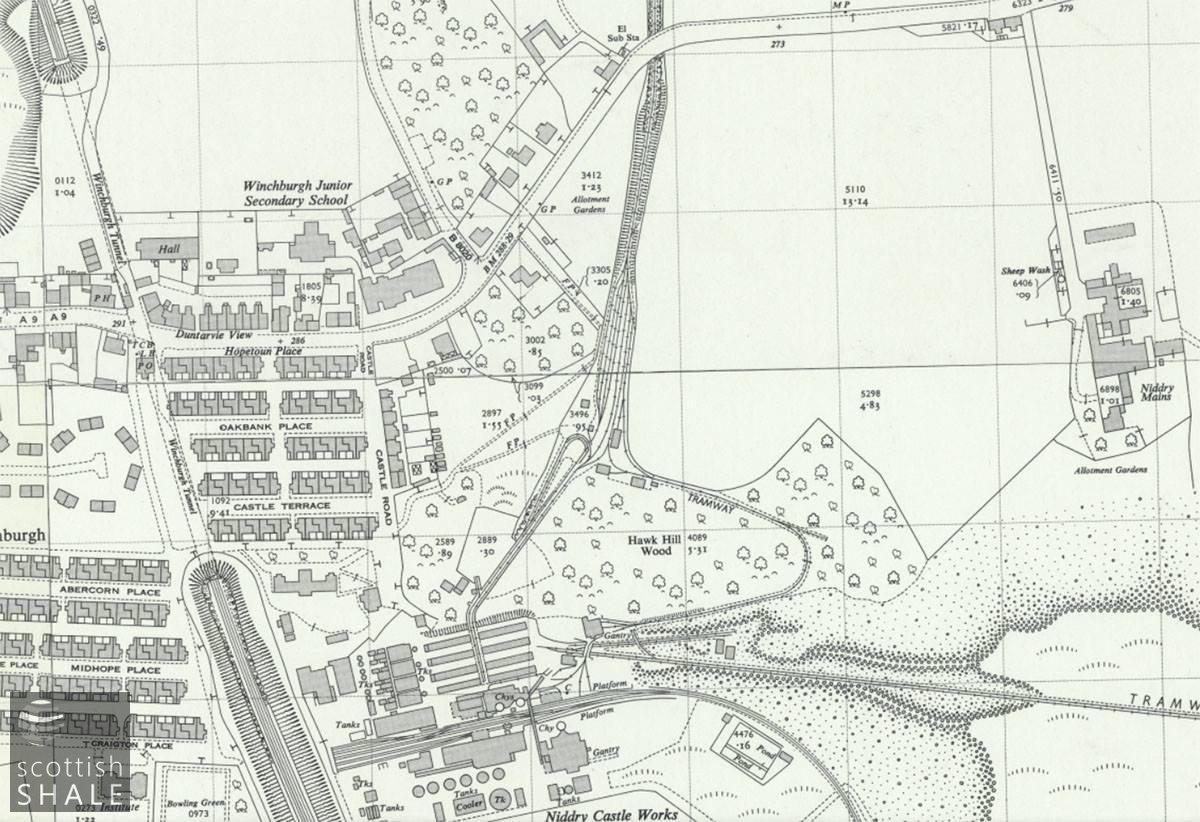

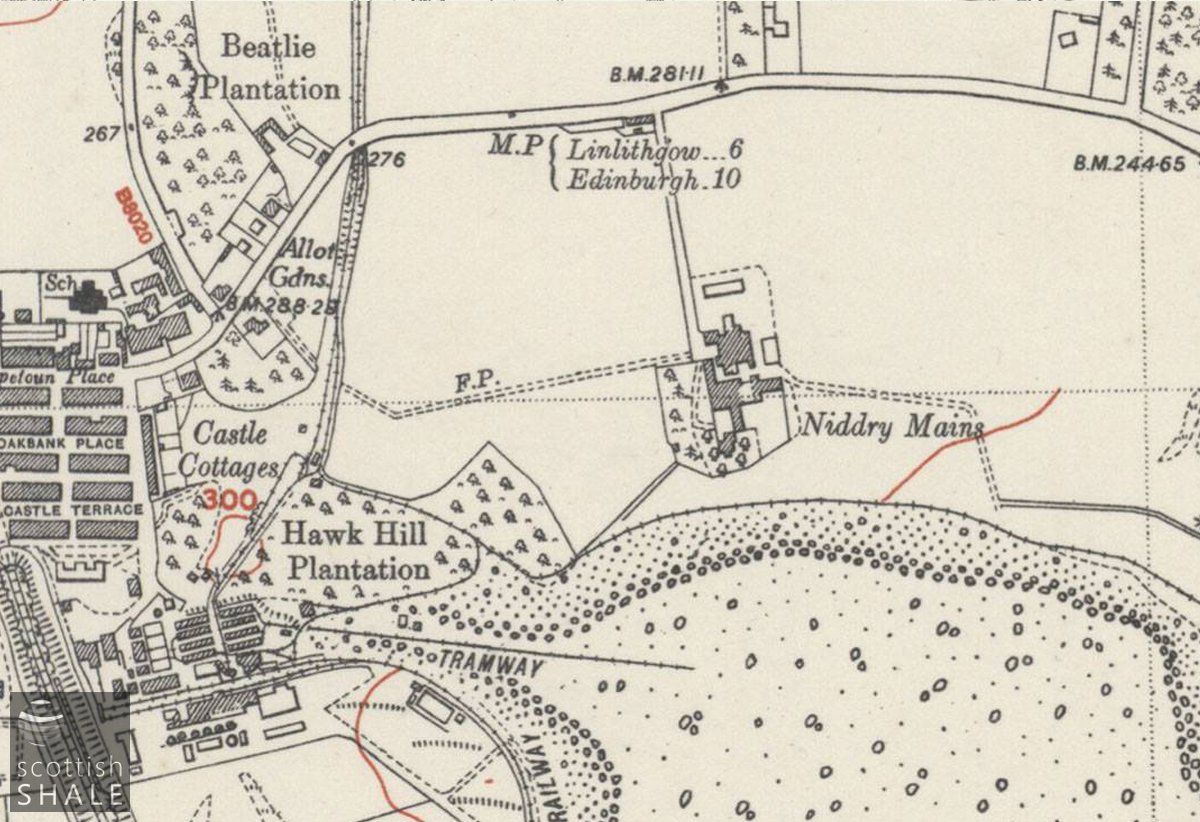

The terminus of the Winchburgh electric railway

The railway in operation - probably looking towards the cutting and overbridge.

The reception sidings, looking north - with rake of hutches and "passenger coaches" for miners.

Small loco shed, with route curving left through Hawk Hill Plantation.

F18019, first published 21st April 2018

It is almost sixty years since the Niddry Castle oil works closed, and with it the little electric railway that linked the works to shale mines at Duddingston, Totleywells and Whitequarries. Although the site of works has been cleared and much else has changed, you can still follow the route of the railway, (and find other evidence of the trains that passed), in the woods to the west of Winchburgh.

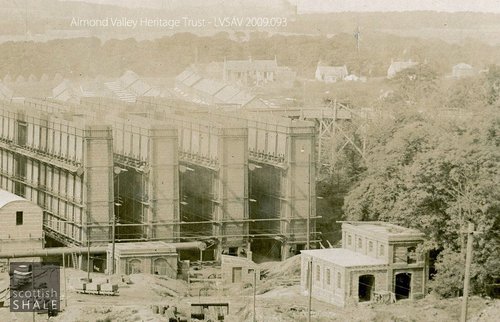

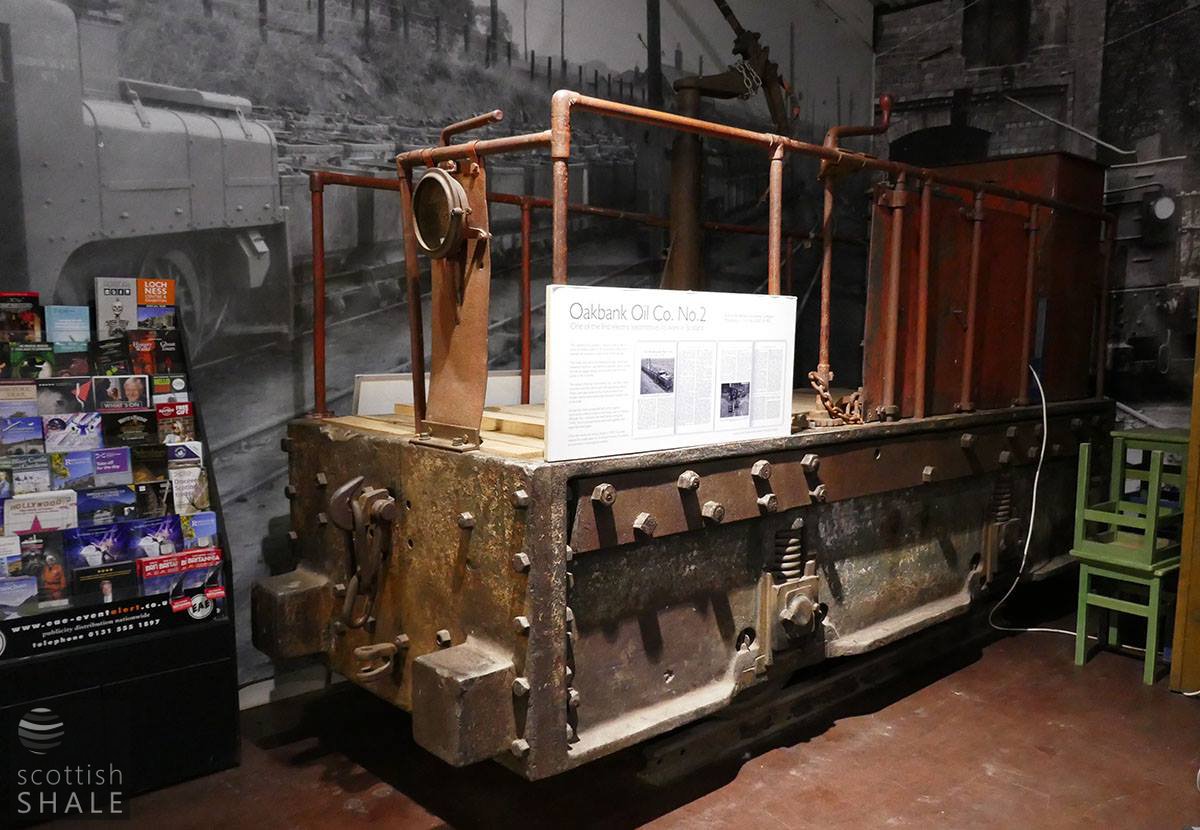

The Niddry Castle works were part of a bold scheme by the Oakbank Oil Company to exploit the oilshale that lay deep beneath the Hopetoun estate. Estate factors were keen to avoid any intrusion of industry on the Hopetoun policies, and required that the shale be transported several miles to the south, where an oil works and workers rows were built at Winchburgh. When constructed in 1902, Niddry castle works were notable in their pioneering use of electrical power, and this innovation extended to the adoption of electrical power for the narrow-gauge railway, which was supplied by overhead wires carrying 600V DC. This represented cutting-edge technology for its time, and the two electric locomotives, (the first to work in Scotland), had to be imported from the USA. The railway carried shale from the pits, and miners to their work, for over half a century, and always remained a novelty and an object of affection.

Much of the route of the railway has been obliterated, but the line can easily be traced from the steep whinstone cutting that passes beneath Winchburgh Main Street, southwards at the foot of the allotments, to the site of the oil works reception sidings. Here the electric locomotives would be uncoupled from their train and the hutches allowed to run, one by one, to the foot of the slope. Each hutch would then be linked to a continuously moving chain running on a pulley arrangement said to be “similar to that found on the fairground big dipper” before being discharged into the shale breaker. Sadly no evidence remains of this wonderful machinery, or the steep incline and timber trestles that once carried hutches of broken shale at tree-top height to feed the shale retorts.

The curving route of a single track of railway can still be followed through Hawk Hill Plantation from the reception sidings to the site of the engine shed. It’s a green peaceful place where it’s not hard to imagine the spark and splutter of the little electric engines as they trundled home through the trees at the end of a busy shift.

Above right: Close up view of Niddry Castle oil works from the bing, showing high level trestle through the trees on the right, transporting shale to the top of the retorts. The brick building on the right is the electric railway loco shed.

Railway cutting where the electric railway passed beneath the B9080, Winchburgh Main St.

Railway cutting looking north towards B9080 bridge.

Route of electric railway through the allotments - curving to the right.

Pioneering technology from 1902 - At Almond Valley.

Section of railway from the electric railway, in undergrowth near the cutting.

Steel buffer cap - a piece of a hutch.

More relics from the undergrowth - a broken brakeshoe from a hutch.

A piece of lightweight hutch rail, reused as a fence post.

Remains of steps - perhaps those seen to the left of the previous image of the reception sidings.

Site of the reception sidings, looking south.

Curving route of the line through the plantation to the engine shed.

Route of railway at the foot of the bing.

Route of railway at the foot of the bing - passing Niddry Mains farm.

In the woods close to Castle Road - the remains of an air raid shelter?

The path of true love, leading to the "air raid shelter".