Just an Ordinary Broxburn Riot

Sectarian hatred, or just a drunken brawl?

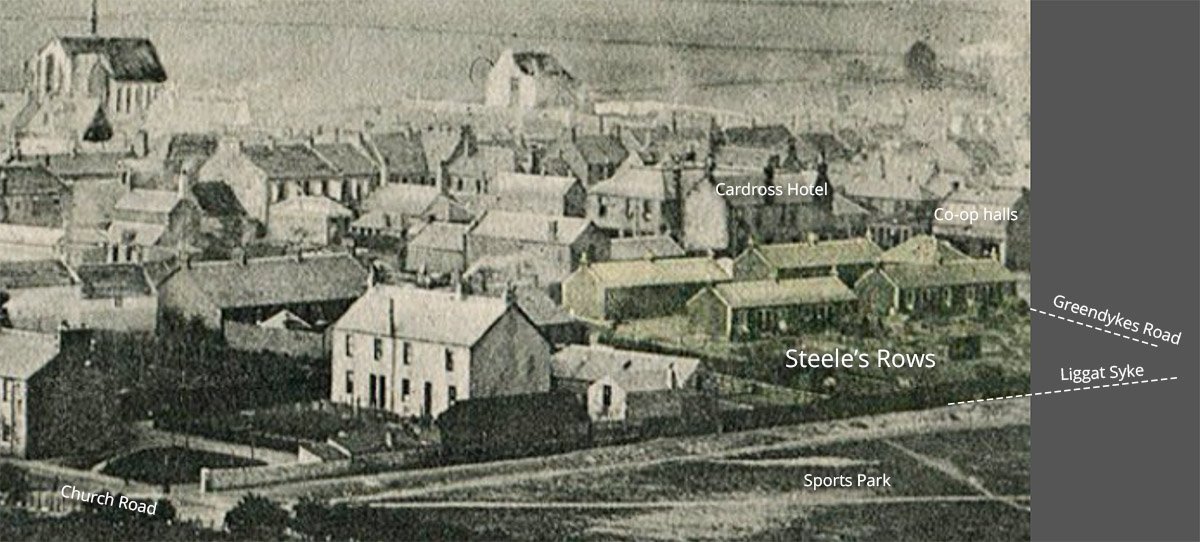

View looking south, probably from an elevated position in Stewartfield bing, c.1905, with the houses of Steele's Row highlighted. See full record LVSAV2013.057

F22001, first published 1st January 2022

In the early 1860’s Broxburn was a boom town. Just below the surface of local fields, seams of a black shale had been discovered that could be transformed into valuable crude oil. The promise of riches quickly brought an influx of fortune hunters and adventurers to the once quiet rural village.

It was a Wishaw coalmaster, Robert Bell, who first realised the value of oilshale. He held the mineral rights to Earl of Buchan’s lands around Broxburn and soon set up his own mines and oil works. He also encouraged other men of business to establish their own oil works in Broxburn, taking a share of their profits in various ways. A newspaper account of 1865 brilliantly describes a chaotic industrial landscape dotted with deep pits and spoil heaps, and “by the flaring brick buildings where the paraffine oil is distilled” Deeply rutted roads were a sea of sticky mud, with puddles reflecting the iridescent flash of oil. Housing was basic and overcrowded, with men crammed together in temporary huts, farm outbuildings, or the few cheap and hurried constructed rows built by the oil companies.

The boom was short-lived, and as the price of oil plummeted, fortunes were lost and many oil works were dismantled after only a couple of years of production

James Docherty was killed in September 1869. By that time there had been some resurgence in the oil industry, attracting new workers to Broxburn from throughout Scotland and Ireland. But it remained a rough and rowdy place, boasting one public house for every four hundred inhabitants.

James Docherty was 25 years old and had moved from Ireland in search of work. He occupied one of Steele's rows; four short rows of buildings, each with four single-room dwellings that had been built to house the workforce of Steele's oil works. The one small room was home to James, his wife Bridget, his 18 month old baby, three lodgers, plus, on the night of the incident, “four men who had been at the harvest”.

At that time, working men were paid only once a month, on a Saturday. A night of stramaash and stooshie usually followed, as folk soaked up the bevvy after weeks of drought, however it seems that things got particularly out of hand when wages were paid on18th September 1869, when events led to James Docherty's death

Local newspapers carried the sensational headlines “Broxburn Outrage – Man Killed” and reported how James Docherty, a “quiet, inoffensive man” who was a catholic, confronted “a large number of Orangemen” intent in forcing their way into home. A mob shouting threats against “the Fenians”

seized Docherty, knocked him down, and kicked him in a “most unmerciful manner,” He later died from his injuries. The newspaper report presented this as a most repugnant sectarian murder. A crime fuelled by hate and intolerance.

Seven men, all protestants, were arrested for murder and rioting, and the following January appeared for trial at the High Court. However the proceedings revealed a rather more complicated story than reported in the press.

Witness statements were presented by many of the lodgers and guests present in James Docherty's house that evening, all of them from Ireland. A written disposition made by Dochery on his deathbed, was also read to the court, and the prisoners, including James Abbott, Docherty's next door neighbour, also gave evidence.

It is clear that a great deal of alcohol had been consumed that night in White's public-house, only a minute's walk from Steele's Rows. Recollections were confused, no doubt due the vagaries of drink, but it seems that the Irishmen gradually staggered back to Docherty's home, while a group of protestant friends congregated in the house next door; the home of James Abbott. A “glass of sherry in a bottle” had been brought back for Mrs Dochety's enjoyment, and doubtless most other parties were well armed with carry-outs. The thin walls between the two houses will have offered little privacy. It was claimed that one of Docherty's lodgers had assaulted one of Abbott's guests which prompted a prolonged drunken hubbub in the street outside, At one point some of Abbott's guest's came to Docherty's door, frank discussions took place, but eventually all parties shook hands, promising to redress any wrong-doing in the morning. But as drink continued to flow, passions became inflamed once again, and repeated knocking at Docherty's door became increasingly forceful to a point where it became clear they would break their way in.

James Docherty, who was described as “a large strong man”, seems to have remained fairly sober throughout the evening. When his front door was about to be kicked in, he fearlessly confronted the drunken abusive rabble that had assembled outside his house. He was cruelly set upon, knocked to the ground and kicked repeatedly in the head, chest and throat. A crowd of 200 had gathered to witness this entertainment, although strangely few saw things clearly enough to be able to identify the attackers. When she realised what was happening, Mrs Docherty rushed outside, lifted her husband off the ground by the oxters, and guided him back to his house. A policeman arrived at this stage, and a doctor was summoned.

Docherty had clearly suffered injury to his face and chest . His throat was swollen, his voice had changed, and he was struggling to breath. It was later discovered that broken ribs had pierced his lungs. It took him three days to suffocate, and died in his small and crowded room, surrounded by lodgers and visitors, and accompanied by the chatter and noise of the neighbours next door.

It took the jury just 20 minutes to come up with a not proven verdict, and all prisoners were released without charge. In summing-up, council for the defence suggested that the incident was “just such an ordinary riot or brawl as might occur at any time in a place like Broxburn” and that the fatal injury was “due to nothing more than the unintentional tumbling of the crowd”.

Folk continued to be born and to die in Steele's row until 1936, when the slum housing was cleared to make way for the magnificent new Regal cinema. In recent years this too has made way for a new Lidl supermarket (now a B&M store) whose footprint covers the whole of the site of Steels Rows. It's strange to think that the space between the bags of compost and the display of discount mop buckets was once home to more than 150 people, and was the scene of so many adventures.

25" OS map c.1913, with Steele's rows highlighted and overlaid on a modern aerial view. All of the rows fit within the footprint of the B&M store.

A rainy day in Broxburn looking south along Greendykes road, with the B&M store on the site of Steele's Rows. Beyond this, "The Club" once the Cardross Hotel, was perhaps constructed on the site of White's public house.