The Lost Viaducts of Westwood

Bridges across the Breich Water to the Westwood pits.

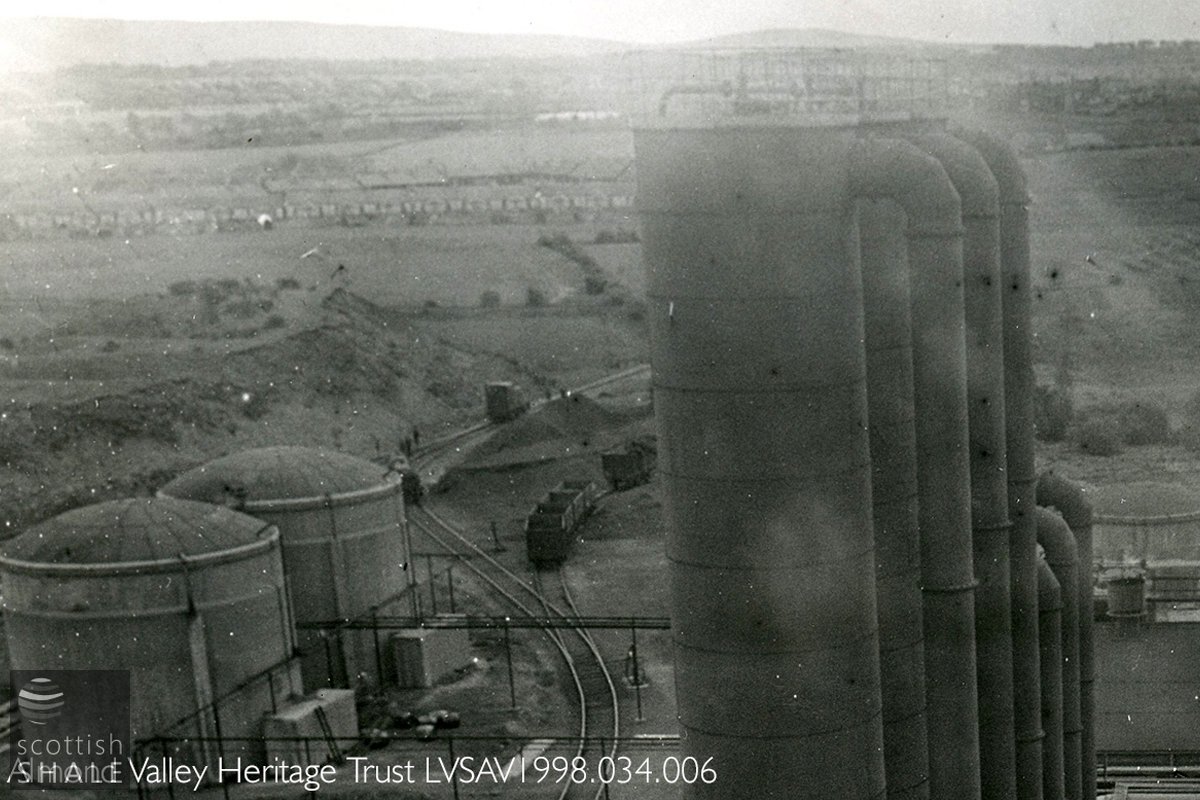

A close-up in the area of the viaduct.

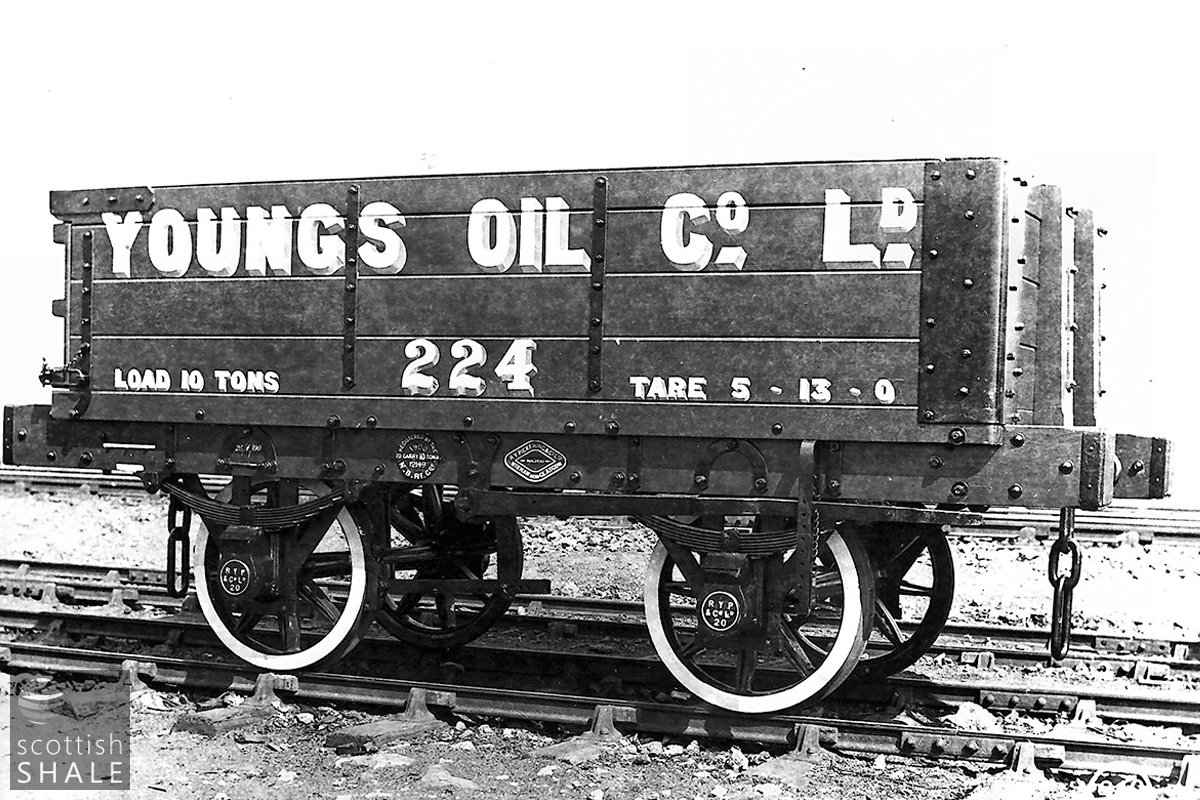

One of Youngs mineral wagons, most likely used for transporting shale from outlying mines along the public railway network to Addiewell or Uphall oil works. The dumb-buffered wagons used on internal railway networks would be generally similar.

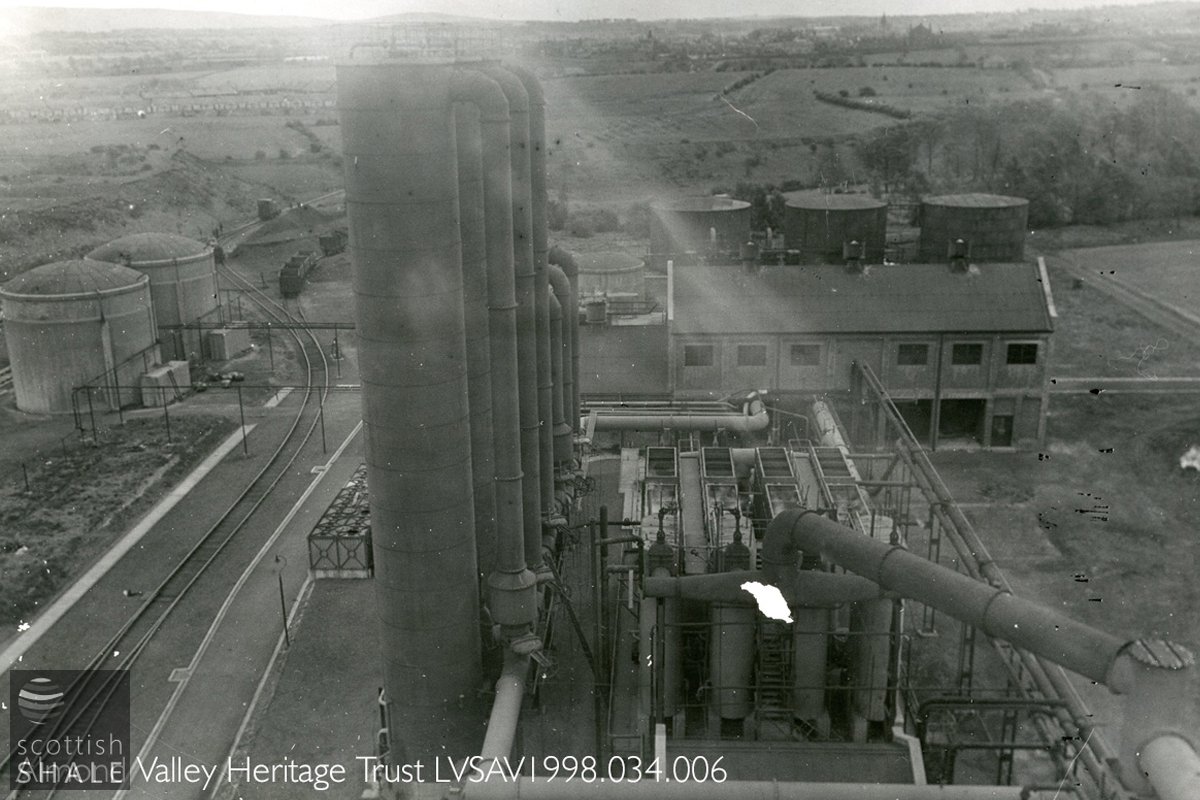

View from Westwood Oil Works c.1950 looking south towards West Calder with the village of Mossend on the left. The works diesel locomotive seems to be on the approaches of the viaduct, hidden beneath the tall naptha distillation towers ?

F19042, first published 1st December 2019

An odd collection of rusty iron and steel, hidden amongst trees on the banks of Briech Water, marks the site of a railway viaduct that once spanned the glen to the lands of Westwood.

The first viaduct at this point was built soon after 1870 when Young’s Paraffin Light and Mineral Oil Co. Ltd. advertised that they were “desirous of receiving tenders for the construction of branch railways from Addiewell works to their shale pits, extending to about two and a quarter miles of single line, with a stone and iron viaduct over the Breich Water, and other bridges”. Young’s began mining shale in the Addiewell area in about 1864, and stockpiled supplies while their new Addiewell oil works were under construction. These first mines were soon worked out, so the company looked eastward to reserves near Polbeth, where they sunk their No. 7, 8, 10 and 11 pits and built Mossend village. The bridge carrying the railway across the Breich Water enabled them to expand northwards into the lands of Westwood where, in about 1870, they sunk their Westwood No. 12 and Westwood No.13 pits.

These were not the first pits on the Westwood estate. The land was owned by the dashing Captain Robert Steuart, who had served in India, and came from an old Scots family. As early as 1864, Captain Steuart had sought invitations to work the “superior bituminous shale, smithy and other coals, fireclay, ironstone and limestone” that lay beneath his estate. He eventually decided to take matters into his own hands, and in about 1866, formed his own company to sink pits and construct an oil works – probably in the western parts of his land near Briechdykes. This was served by a siding from the Caledonian Railway’s loop line, and lay at a respectful distance from Westwood House.

Things seem not to have gone well with this enterprise, and in about 1870 Captain Steuart seemed happy to let mineral rights to Young’s oil company. Young’s new Westwood No.13 pit lay just beyond the wooded policies of Westwood House, with No.12 a little to east. Both exploited the Broxburn shale seam that lay a couple of hundred feet beneath the surface, and were linked by a siding running across the Westwood viaduct to join Young’s private railway to Addiewell. Young’s subsequently sunk a further pit – No.30 – in the eastern edge of the estate, which linked underground to their workings at Polbeth No.11.

Young’s had signed a 21 year lease of the Westwood minerals, and when this expired in about 1893, it was decided to abandon the workings as uneconomic. The OS map surveyed in 1893 shows the viaduct and siding still in place, with mine buildings still standing at No.13 and No.30 pits. By the next edition, (revised prior to 1914), all mining had ceased, the viaduct and railway sidings had disappeared, and only earthworks, bings and a scatter of “old shafts” remained.

The bold and progressive Oakbank Oil Company realised that more than five hundred feet below the old workings in Westwood should lie a rich seam of Dunnet shale. The company acquired the mineral rights to the estate in 1908, and set about sinking a new Westwood pit. This turned out to be the deepest shaft ever sunk in the shalefield, and its development was fraught with problems. It opened in 1915 and continued in production until the very end of the shale industry in 1962, during which period over ten million tons of Broxburn and Dunnet shale were brought to the surface. The Oakbank company built a new siding from the Caledonian Railway loop line to serve their Westwood pit, rather than re-instate the viaduct which still lay in the territory of the rival Young’s oil company.

As World War Two approached, the shale industry received substantial investment to secure supplies of home-produced oil for the war machine. It was decided that a new Westwood oil works be constructed to make best use of the plentiful supplies from Westwood pit. Development of this ultra-modern works (which threw up the five sisters bing) included construction of a new viaduct across the Briech Water, at the site as the original, to provide a second route of rail access to this strategically important facility.

It is the sawn-off steel pier of this wartime viaduct that still pops-up form its concrete foundations on the north side of the Briech Water. Intertwined amongst this are two pairs of wagon wheels – perhaps the remains of a last train that never quite made it across.

Map above shows part of a Plan showing boundaries of the Westwood estate, and the trial bores sunk by the Oakbank Oil company in about 1908. The ground beneath Westwood house and City Farm (marked green)are presumably excluded from the ground lease, as are the abandoned railway and mine sites marked yellow.

Top map: Part of a Plan showing boundaries of the Westwood estate, and the trial bores sunk by the Oakbank Oil company in about 1908. The ground beneath Westwood house and City Farm (marked green)are presumably excluded from the ground lease, as are the abandoned railway and mine sites marked yellow.

Map showing the new viaduct serving Westwood oil works, and a more recent aerial view showing the new houses of Monarch's way underway where small steam engines and their rattling trains of shale trucks once passed.

Map with viaduct and railway in place, and a view following their removal. Image courtesy of National Library of Scotland.

A traditional wagon wheelset, with cast iron hub.

A traditional wagon wheelset, with cast iron hub.

Presumably the remains of a lightweight steel pier which supported the second viaduct, with two wagon wheelsets.

Presumably the remains of a lightweight steel pier which supported the second viaduct, with two wagon wheelsets.

The viaduct site looking east. The rocks on the right bank are presumably the rubble of the first viaduct.

This scatter of large building stones on the south bank of Briech Water presumably comes from the masonry abutments of the first viaduct.