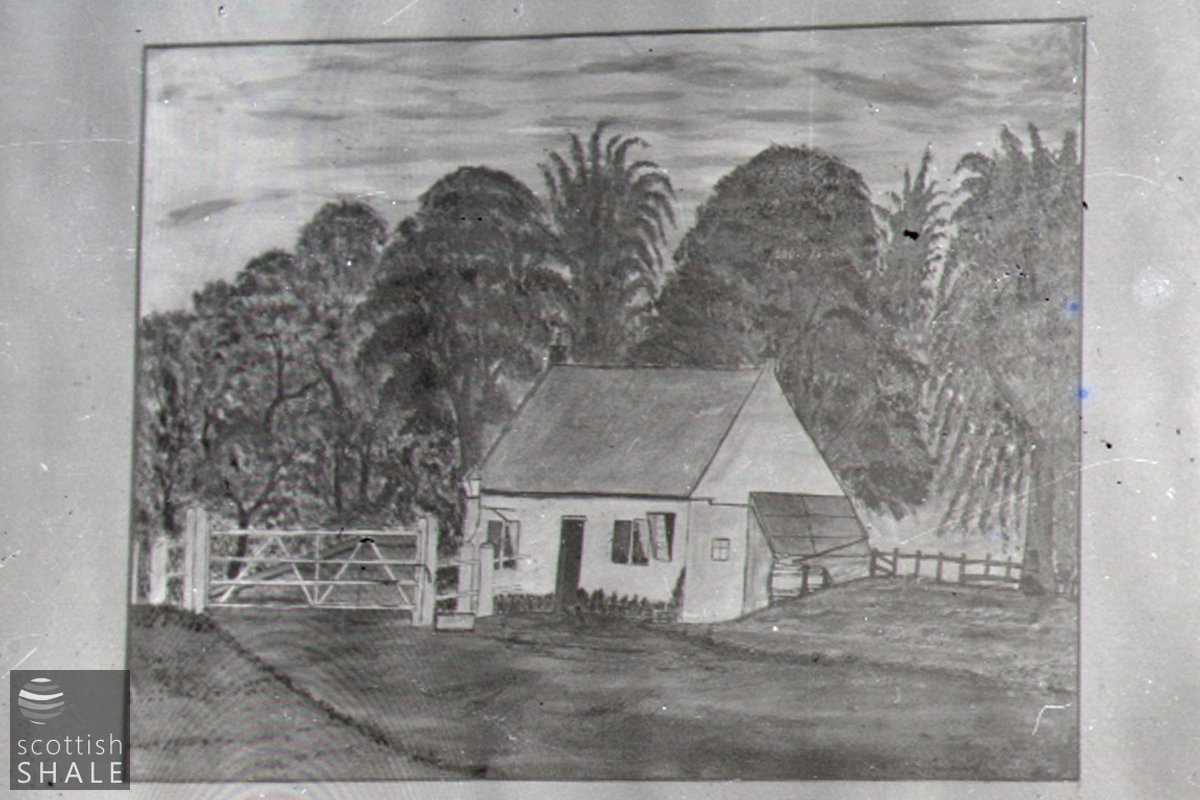

Stampede at Howden Toll

Howden toll on the turnpike road.

F19043, first published 17th December 2019

The construction of turnpike roads during the second part of the 19th century stimulated the growth of commerce and industry, and transformed Scotland's economy. The creation of turnpike trusts allowed capital to be raised for construction of roads and bridges linking Scotland's major towns. Income was generated by charging tolls for the use of these roads which were collected at regular toll bars along each route. The “Great Turnpike” road from Edinburgh to Glasgow via Midcalder, Whitburn and Shotts, was completed in about 1765, and including a fine stone bridge across the River Almond near Howden. A toll bar just to the south of the Howden bridge controlled traffic on the grand turnpike and on lesser turnpike routes heading south and east. A small community grew up around Howden Toll (labelled Kamefoot Toll on one early map) including a smithy to serve the needs of the passing traffic.

A century later, there was growing resistance to the Turnpike system, which was described by some as a “barbarous, antiquated and unfair mode of assessment for the maintenance of the public highways”. A Royal Commission, reporting in 1860, recommended that turnpike trusts be abolished, and that burghs should instead maintain the streets of their towns, while county authorities should be responsible for county roads. Some county authorities promoted private legislation to enable this change, but in many areas, including Midlothian and Linlithgowshire, vested interests ensured that the old system continued, despite many trusts running at a deficit. By 1875, following various amalgamations of road trusts, the Howden toll and road eastward to Edinburgh was controlled by the Calder, Slateford and Corstorphine road trustees, while the main route westward was the responsibility of the Glasgow and Shotts road trust.

Toll bars, and occupation of the houses associated with them, were the subject of regular public roups, which sought best offers for the rights to collect tolls. It was not usual for tolls-keepers to be women, (often widows), as the role provided a home for their children, who in turn would help staff the toll gates at all hours.

The 1871 census reveals that Jane Falconer, aged 38, was toll-keeper and head of household at Howden toll house, which she shared with her three children and her father, Robert Miller, described as “labourer on roads”. It might have been that Jane still held that position in 1875, when a dramatic occurrence resulted in the charging of four local carters. It was alleged that on the 4th of August, at about mid-day, the four approached the gate and forced their way through with a number of horses, with no intention of making payment. According to the young woman who was in control of the gate at that time, the horses galloped through so quickly that it was impossible to count them, although she thought there might have been as many as thirty of them. She was only able to positively identify two of the defendants, who were subsequently fined ten shillings each.

If the Jane Falconer family was still toll-keeper that time, it is possible that “young woman” on duty might have been daughter Marion, who would then have been aged eight years old.

Its not recorded whether the guilty carters simply exploited the vulnerably of the young gatekeeper, or whether their actions reflected a wider disregard for authority, in the knowledge that the turnpike system was coming to an end. The bill to abolish turnpike trusts was passed in 1878, but it was not until five years later that the toll gates were finally removed, and traffic was allowed to pass unhindered.

In later years the toll cottage was home to surfacemen employed by the county council to maintain the stretch of road. The building seems to have survived into the new town era of the 1960's, but will have been demolished prior to the construction of the Almond viaduct. The network of turnpike roads controlled by the toll-bar have, of course, been largely lost beneath the development of the new Livingston.

The Almond viaduct, viewed from the north side of the Almond. The buildings on the left mark the site of Howden smithy, the Howden toll building seems to have been demolished by this time.

Sketch of Howden Toll - From a cottage interior probably dating from about 1920.

A helpful native indicates the site of Howden toll.