Uphall's Bridge of Mysteries

The railway that disappeared

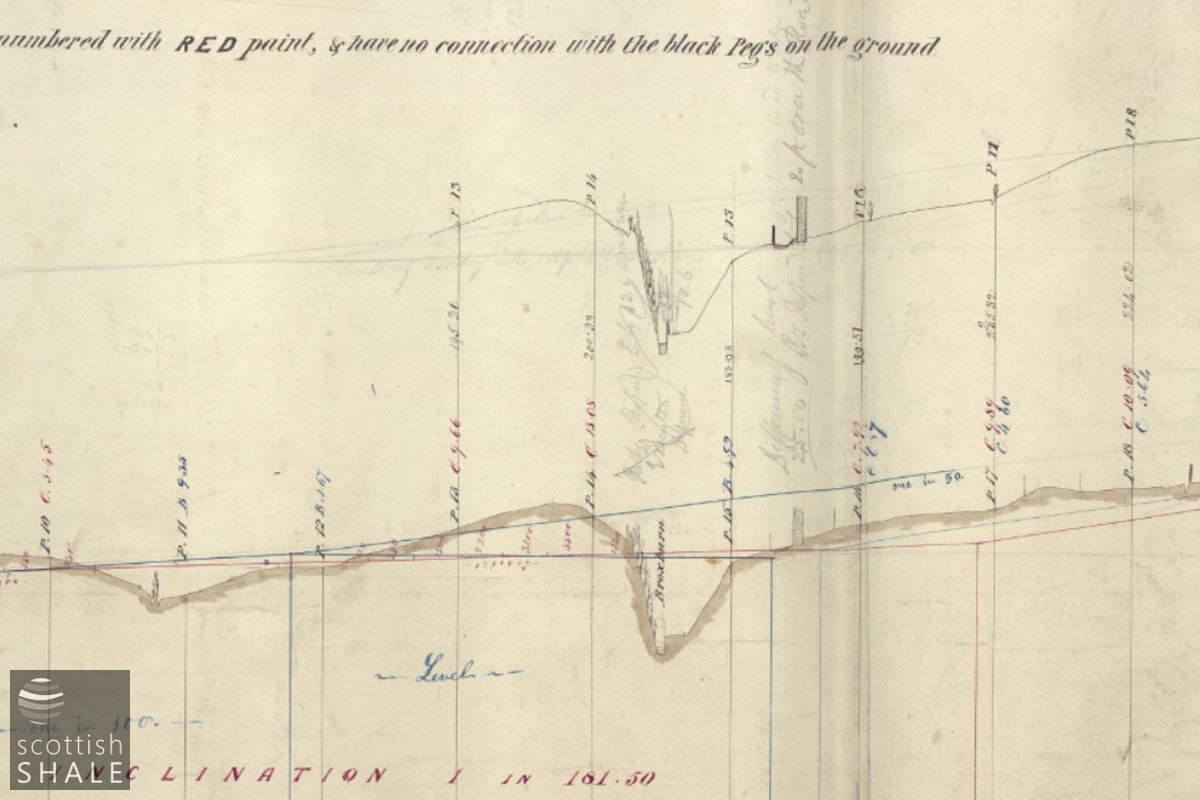

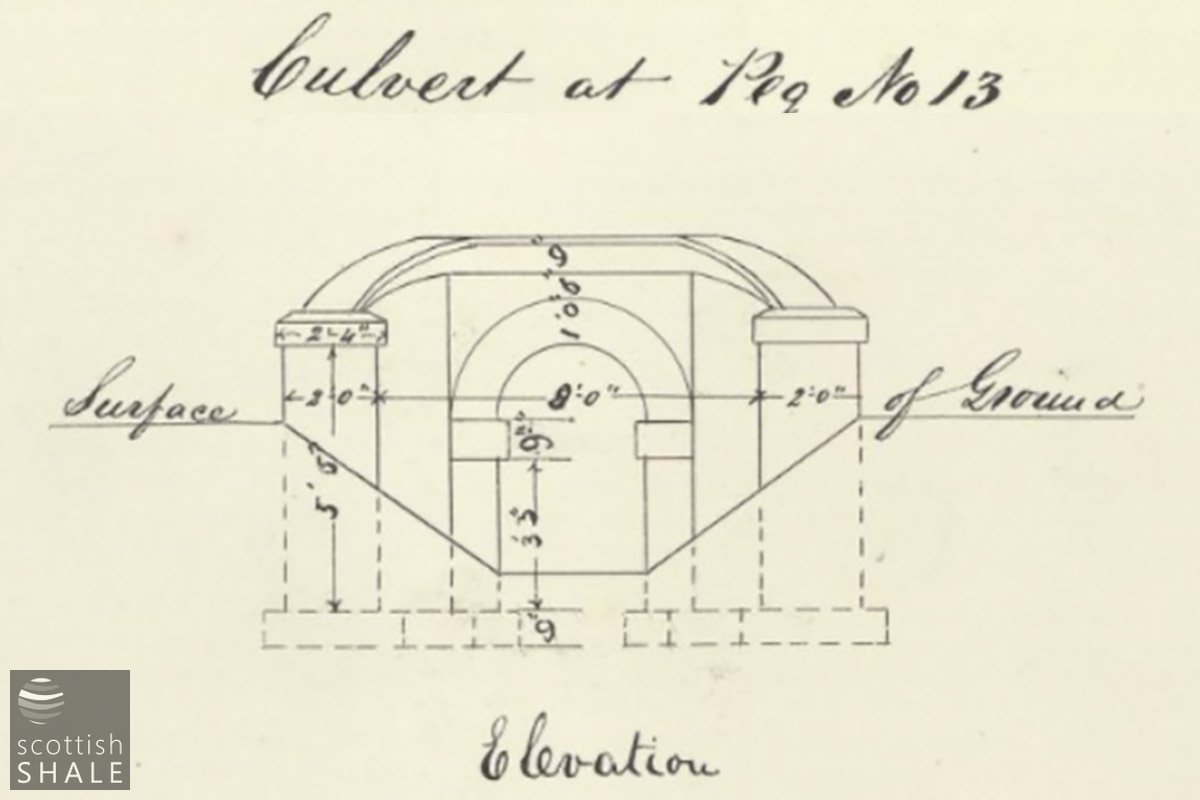

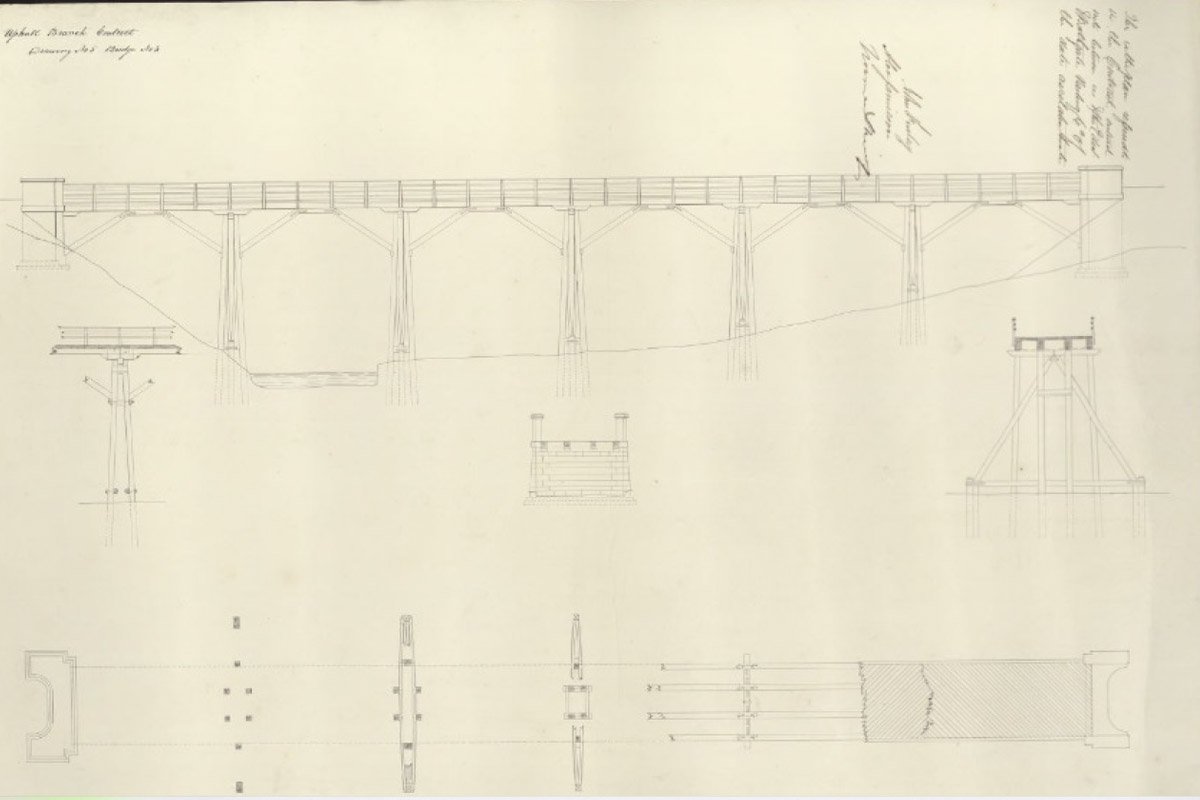

Wooden trestle bridge across the Brox Burn. From the 1847 construction drawings, courtesy of the National Library of Scotland

F22005, first published, 1st March 2022

A handy footpath links West Main Street in Uphall with Middleton Hall, crossing high above the picturesque wooded glen of the Brox Burn before continuing southward, past the Middleton Hall bowling green, and onwards to Uphall Station, The footbridge seems a sturdy modern structure, with fabricated steel railings and deck painted a functional grey colour. If however you gaze down to the burn below, you realise that the bridge spans the gap between substantial stone abutments and is supported on two heavy stone piers that are far wider than the current footbridge. The stonework is a substantial piece of railway-style civil engineering that you might imagine would carry an iron deck wide enough for two lines of railway, Yet there is no record that trains every rumbled across the glen at this point.

From what evidence survives, it seems that the footbridge was on a planned route of railway that was never completed; one small episode in the short but complicated history of the Edinburgh and Bathgate Railway Company.

During the 1840's Edinburgh was in the midst of a building boom. The high quality sandstone from the Binny (or Binnie) quarries was in great demand for some of the city's finest structures, including Donaldson's School, the General Assembly Hall and the Scott Monument. The Binny quarries lay beside the Ecclesmachan road to the north of Uphall, and the many thousands of tons of stone needed for the prestigious Edinburgh projects had to be hauled by teams of horses through the streets of Uphall before being loaded onto canal barges at Port Buchan in Broxburn, two miles distant. A railway connection to the quarry would have made things so much easier, and was a major motive for promoting the Edinburgh and Bathgate Railway .

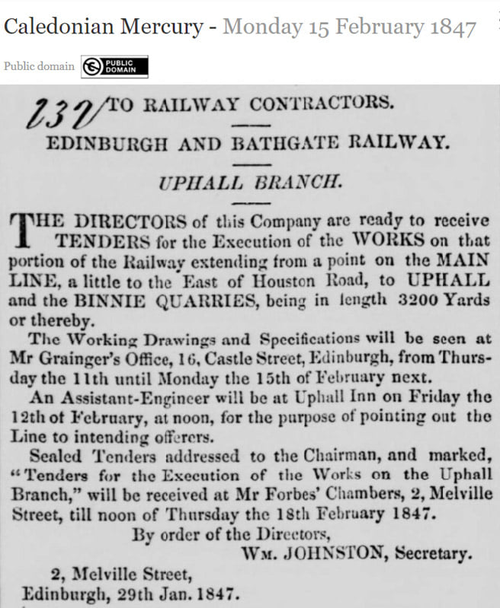

The prospectus for the new railway was published in May 1845. The promoting committee featured many local landowners and industrialists including John Stewart of Binny, who was then convenor of the county of Linlithgow,. Also listed were David Lind, builder, of Edinburgh, the lessee of West Binny Quarry and Walter Gowans, of Gowanbank, the lessee of East Binny Quarry. The E&B main line diverged from the recently opened Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway at a point near Ratho, and following a route to Bathgate which was promised to be an “almost straight line”, and “very nearly level throughout” The Act of Parliament permitting construction of the railway received Royal ascent in August 1846, and included powers to construct a branch to the Binny quarries; also a branch to the Midcalder and the Camps limestone quarries, and another to Blackburn and Whitburn (plans for which were subsequently extended to Benhar and Shotts).

A first sod ceremony marking the start of construction works took place in a field near Miekle Inch just to the east of Bathgate in April 1847. Thomas Grainger, the engineer appointed to plan and build the railway, presented a silver spade to the wife of Chairman John Stewart, expressing the director's wish that “the spade should be conveyed to Binny, to be retained as an heir-loom of the family”.

It was never the intention that the Edinburgh and Bathgate Railway should run its own trains, and from the outset it had been agreed that the line would be leased to the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway for a period of 999 years. The relationship between the E&B and the E&G however was never a happy one and proved a constant source of drama and litigation until both companies were merged into the North British Railway in 1865. The E&B board included directors who were nominated by the E&G, and there were accusations that funds raised to build the E&B were being syphoned off by its partner. At one point two rival groups of shareholders were holding their own meetings, and during another dispute, the E&G suspended train services for a while as a sanction against the E&B.

The continual squabbling and expensive court cases must have drained the company's energies, Although detailed plans were drawn up for the various branches, a practical start was made only on the branch to Binny quarries. An incomplete set of construction plans for the Binny branch survive in the National Library of Scotland. These are dated 1847, although various pencil notes and scribbles give clues to how ideas subsequently evolved. The plans include a wonderful sketch of a timber viaduct seemingly to carry the line to Binny across the deep glen of the Brox Burn. Early in 1847, contractors were being sought to built the line to Binny, however by the end of the year, reference was being made only to the “Uphall branch”, suggesting that the Board were back-pedalling on plans to progress beyond Uphall . In March 1850 the Board resolved “not to proceed further with the Uphall and Binnie branch in the meantime, than to the turnpike road at Uphall”. It was later alleged that the Edinburgh and Glasgow company had “joined their interests with the Union canal” and consequently “stopped the line at Uphall, leaving all the stone from these quarries to be conveyed, as formerly, by canal”.

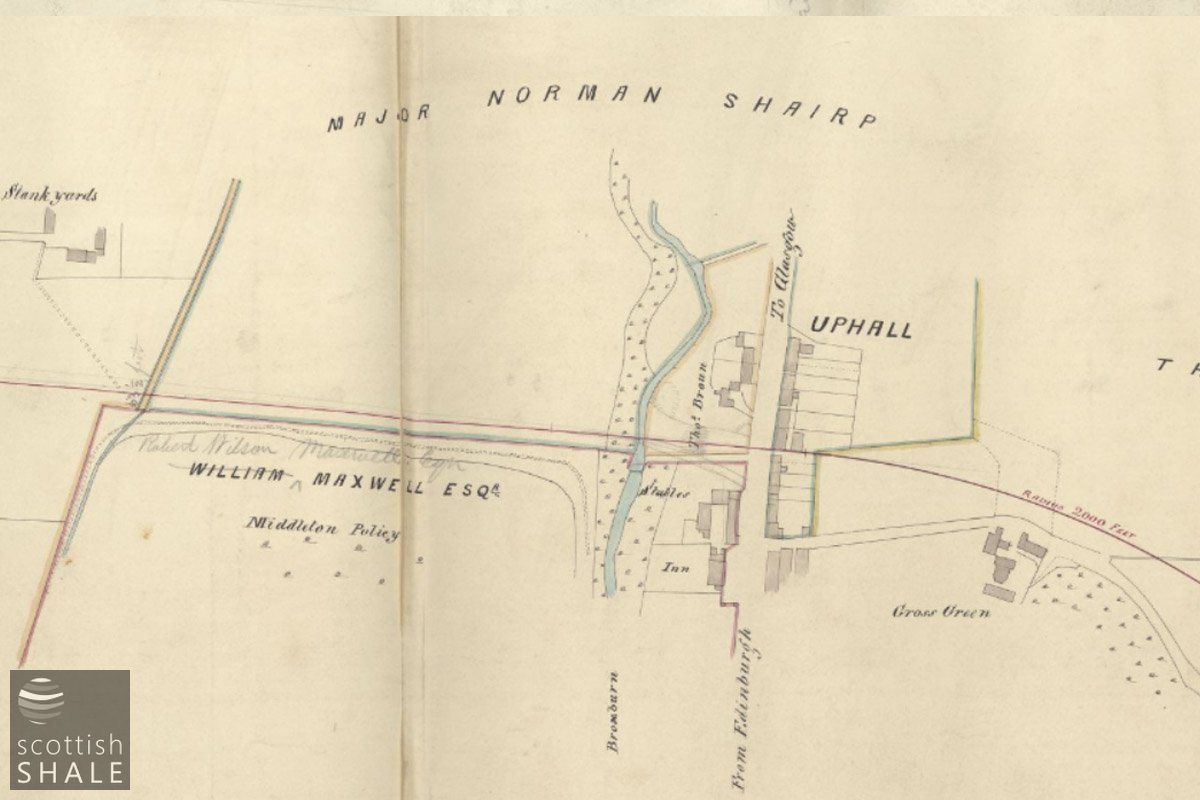

A new parliamentary bill approved in 1847 had included powers to alter or deviate the Uphall branch, It might be imagined these included a deviation to create a depot beside the turnpike road in Uphall, and change the connection to the main line so that it faced Bathgate, rather than facing east as would have suited the transport of stone to Edinburgh. In March 1849 it was reported that the Edinburgh & Bathgate had now acquired the whole land and materials requisite for the formation of the main line and Uphall branch, and in October 1850 it was announced that works on the Uphall branch were completed, “in so far as these are intended, for the present, to be carried out.”

It seems however than no train service ever ran along the branch, At a E&B shareholders meeting in September 1852, Mr. Greig, a director of the the E&G, expressed the view that the money laid out on the Uphall branch was ”a total loss, as it was altogether unused, and his had been almost the only engine which had passed over it”. It seems that E&G directors often jollied around their network in their own private inspection saloon.

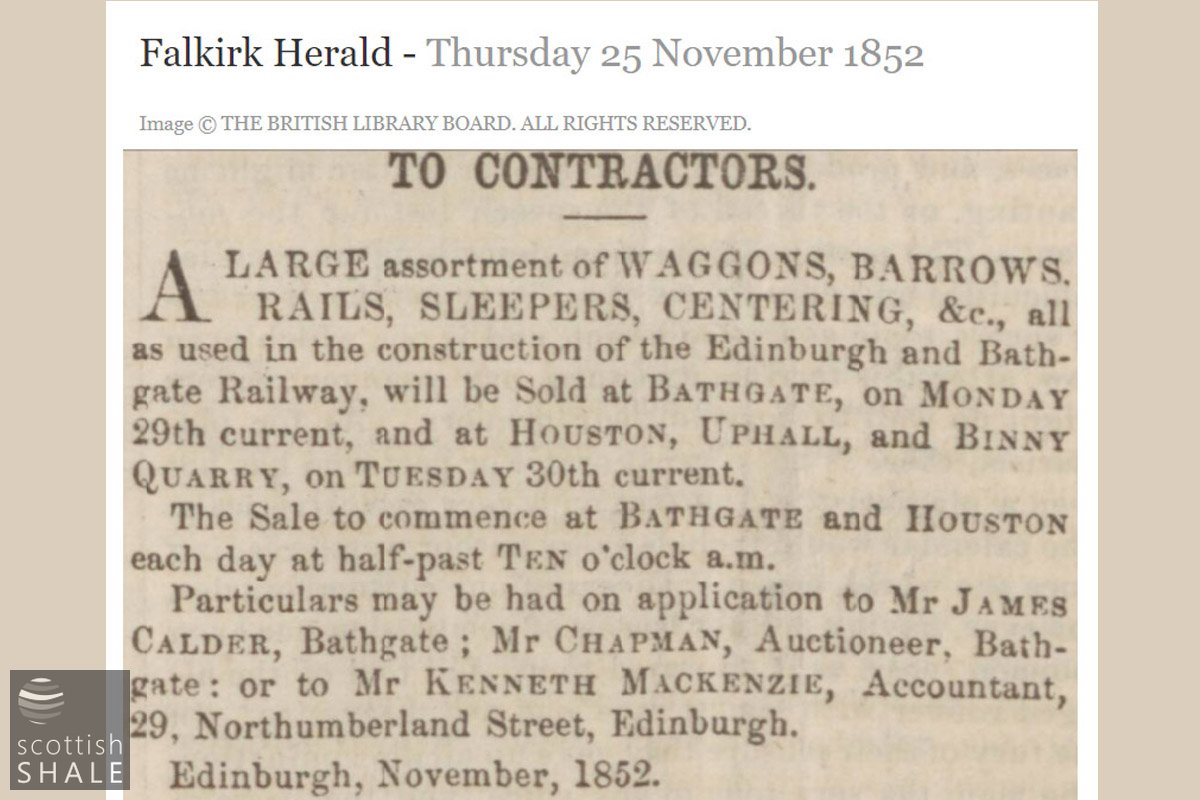

During a further round of wrangling with the E&G in February 1855, it was reported that “a short time ago, the lessees of the line (i.e. the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway), had suddenly taken away the rails and sleepers of the Uphall branch; and on complaint being made of this, they were told that they would be restored at the end of the lease”. This seems to have been a bit of legal joke as the lease had another 995 years of so to run...! Legal counsel advised the E&B board to take action against this flagrant theft of their property, but there is no record that the rails were ever reinstated.

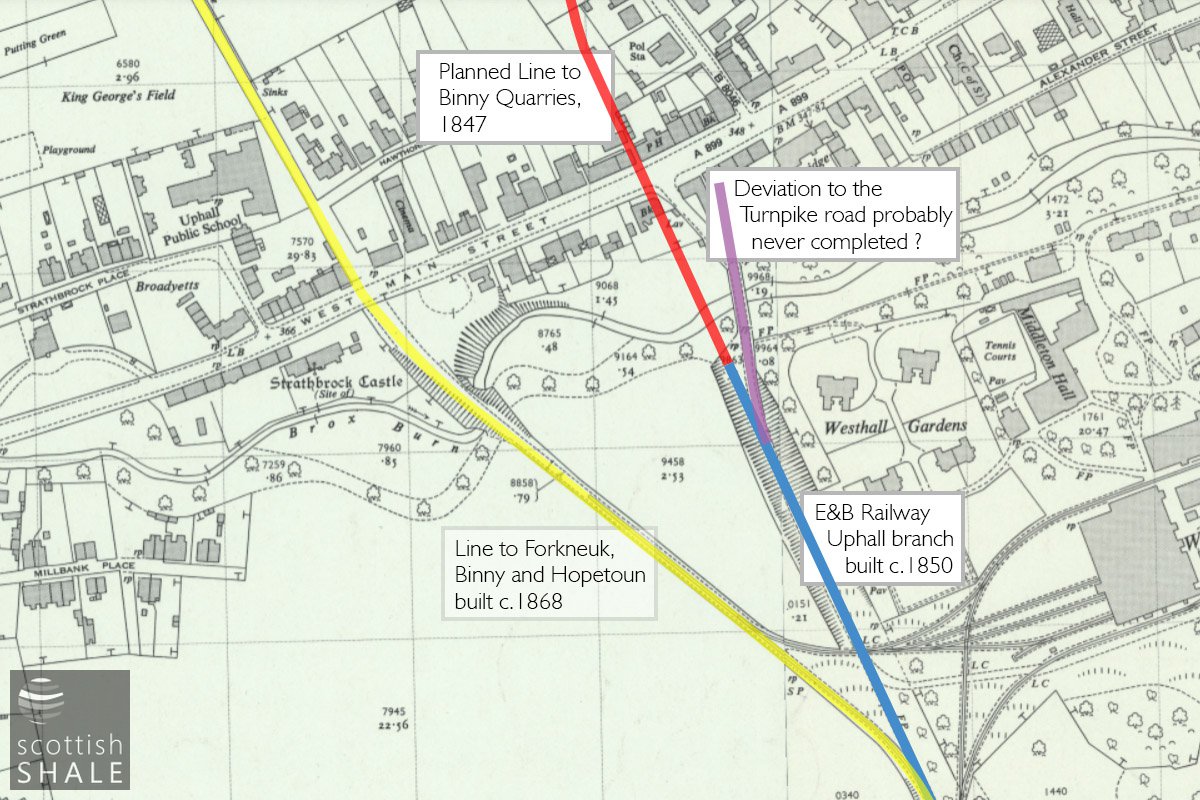

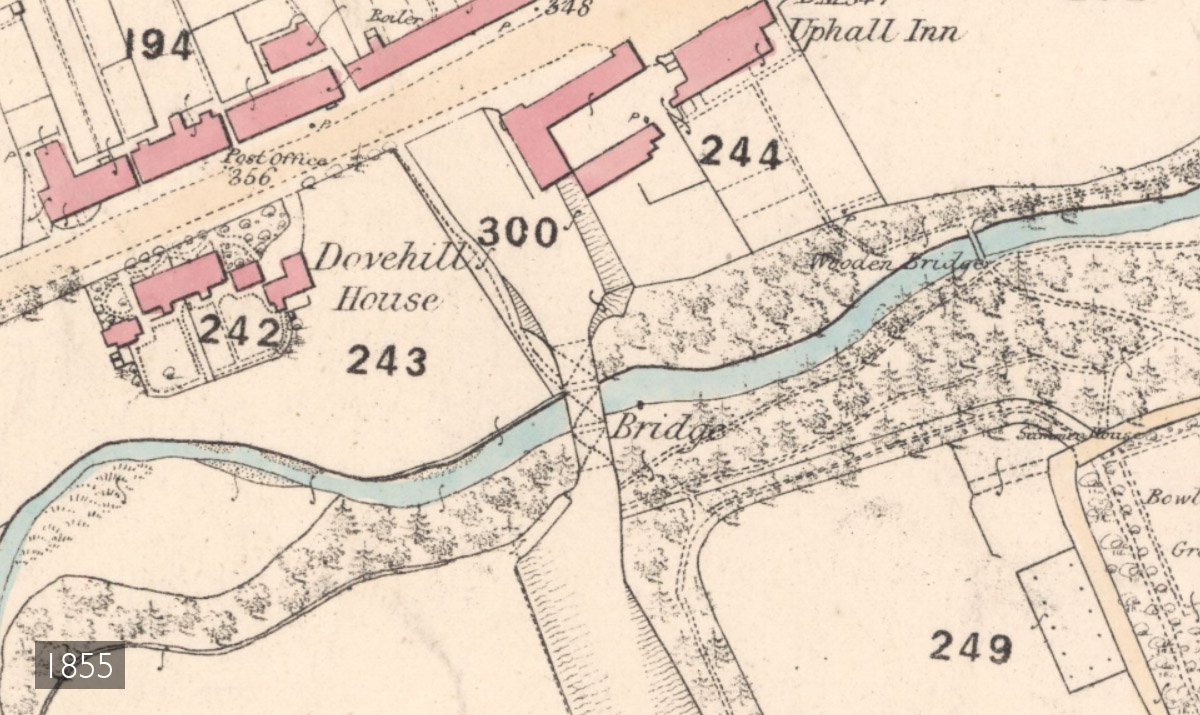

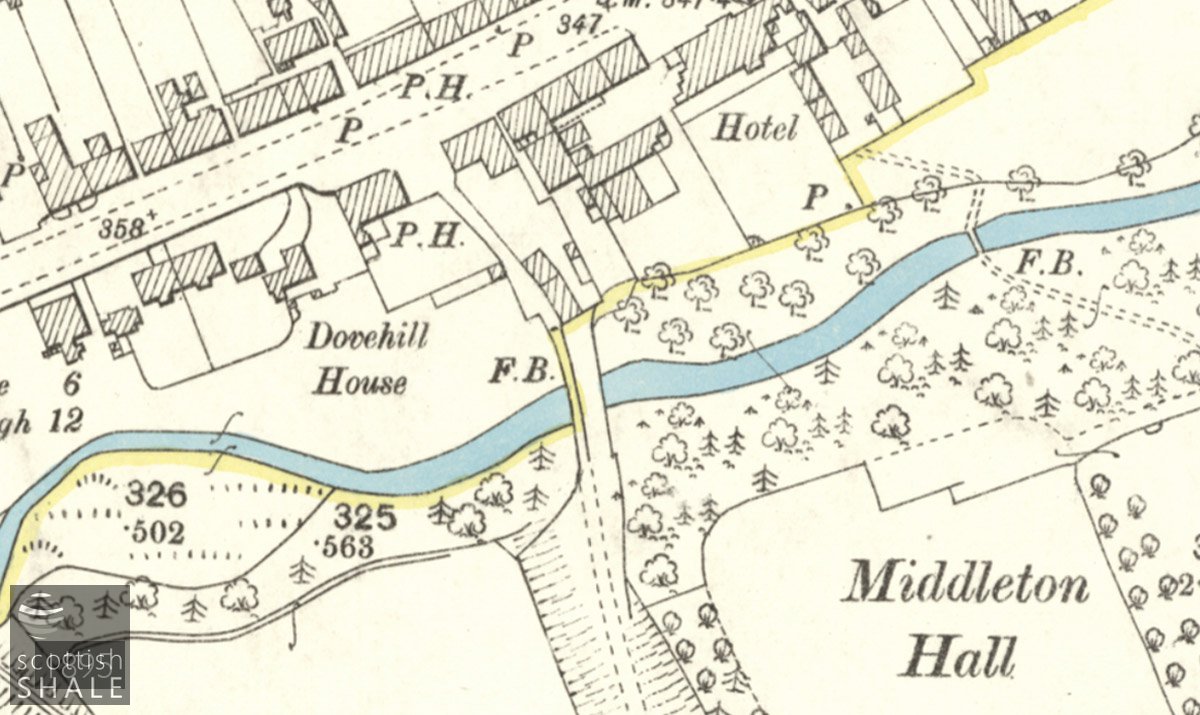

The 1855 Ordnance Survey map shows a well engineered trackbed with bridges, culverts and a substantial cutting south of the Brox Burn; all devoid of rails. The straight route the railway ended abruptly when it reached the Brox burn, however a bridge is marked immediately to the east of this point, and set at a slightly oblique angle. The map shows the wide abutments and piers of the bridge that exist today, but with puzzling crosses marked between them. This might suggest that the bridge remained incomplete, and without a deck. It seems likely that the bridge was intended to serve a goods station fronting onto the turnpike road (now West Main street ) that was never constructed. By 1895 a narrow footbridge had been constructed across the Brox Burn, supported on the masonry piers of the old bridge

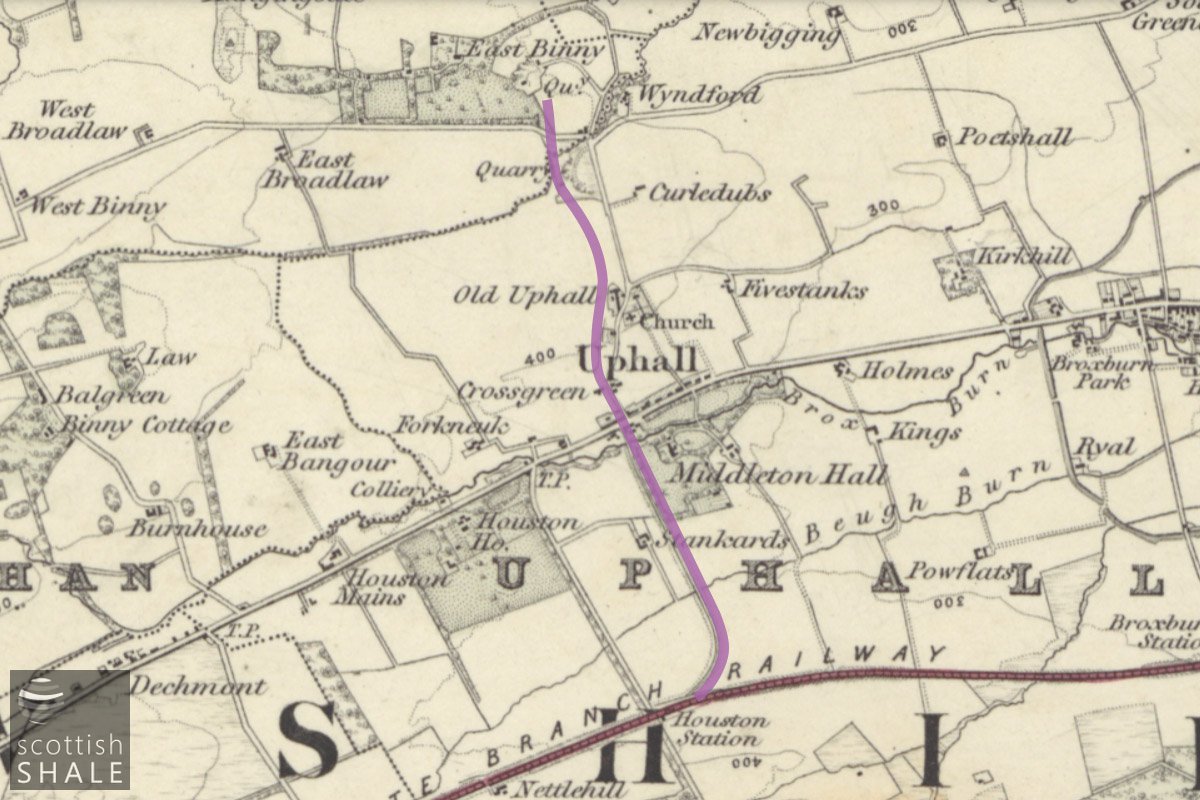

In about 1866, the Uphall Oil Co. (later Young's) began construction of their Uphall oil works at a point close to where the Uphall branch had left the E&B main line. Shortly afterwards, the company build a second crude oil works at Hopetoun, near Niddry, and constructed a three mile long railway to link the two works, Rails were reinstated along the old Uphall branch up to a point close to the present site of Middleton Hall bowling green, where the line headed off on an new alignment around the western edge of Uphall village. The route then followed a wide sweep around their Forkneuk shale pits and passed the Binny quarries, which by then were close to exhaustion. The oil company took out various land leases to make this possible, some of which were not relinquished until the last shale oil interests were wound up in the 1960's

25" OS map c.1855, courtesy National Library of Scotland

25" OS map c.1895, courtesy National Library of Scotland

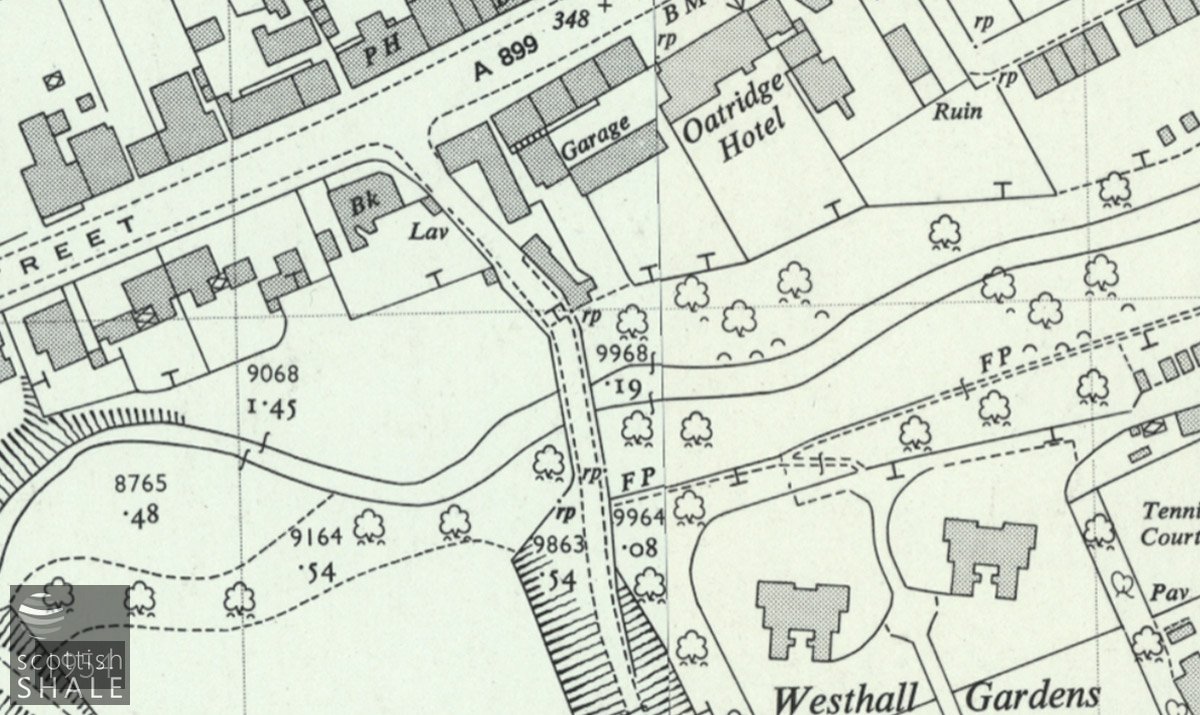

25" OS map c.1913, courtesy National Library of Scotland

1:2500 OS map c.1954, courtesy National Library of Scotland

All this history was forgotten until a day in 1970 when members of the Middleton Hall bowling club were confronted by men from British Rail intent on installing the concrete posts of a fence stetching across the road that provided access to the bowling green. It appeared that after more than the century, the railway authorities were reasserting their ownership rights. A helpful British Railways offered the bowlers an inexpensive lease of the land outside their clubhouse, but required that they also take responsibility for maintenance of the footbridge across the Brox Burn which at the time was in a dangerous state and cordoned off....! West Lothian District Council then came to the rescue, buying the land and bridge from British Railways, and eventually fitting a new superstructure and deck.

Today the footbridge provides a vital link between parts of Uphall, while the railway cutting to the south is well-used thoroughfare set among greenery and trees, It forms part of the Shale Trail. The sturdy stone retaining walls within the cutting, and the abutments and piers of the bridge, seem as sound as when they were constructed over 170 years ago; a solid memorial to an odd railway that never saw a train.