Knock oil works

The Creed chemical works once produced tars and oils from peat on moorland west of Stornoway on the Isle of Lewis. This unusual venture was bankrolled by the island's owner, Sir James Matheson, and operated between 1857 and 1874. The novelty of this peat-processing technology, and its unexpected location, attracted a great deal of public interest and was the subject of various newspaper accounts. This however, was only part of the oil manufacturing process, and most of the crude products from Creed were then carted through Stornoway to be refined at Garaboost, six miles to the east.

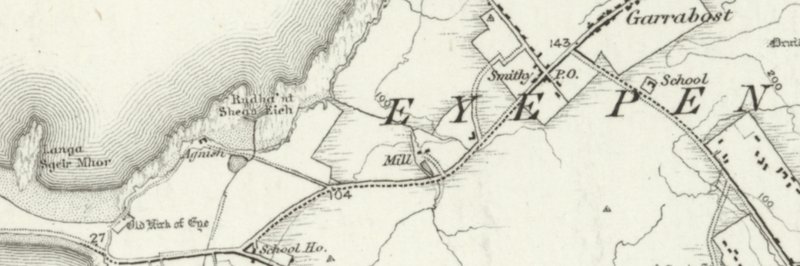

Garrabost lies on the Eye peninsular, attached to the main body of Lewis by a narrow neck of land. It is a landscape of crofts and moorland, on gentle slopes falling down the sea. A fine iron-rich clay found beneath the fields of Garaboost was the subject of James Matheson's first industrial enterprise on Lewis. In 1847 he constructed a large brickworks there to provide many of the bricks needed in the rapid development of Stornoway town, and the tiles required for land-drainage and agricultural improvements. The brickworks were fired with coal imported through the port of Stornoway, and it was presumably considered most practical to refine the peat tars at Garraboost, where there were existing steam boilers and large covered areas of drying sheds.

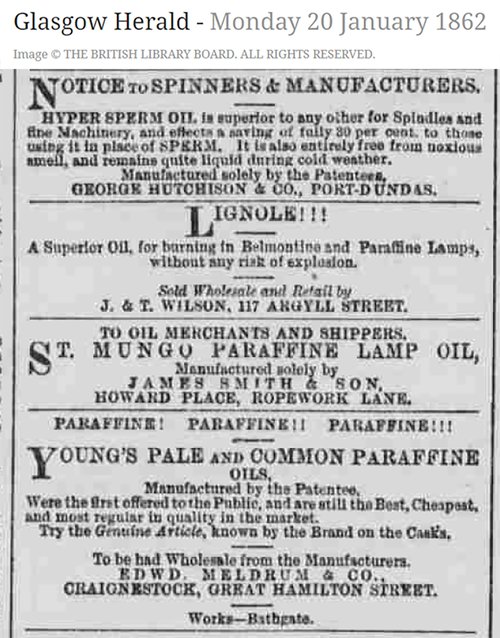

Oil refining was already a well-established technology, and the fractional distillation of crude oil was not that dissimilar to the familiar process of distilling whisky. The initial fraction collected from the distillation process was a described as “a light pale yellow oil with a slight and not unpleasant smell” which “burnt well in the lamps commonly used for hydro-carbon oils” This lamp oil was marketed under the name “Lignole”. This brand was first sold though agents in the Glasgow area during the winter of 1861, and was introduced at a time when Young's Patent Paraffine Oil had recently become the established market leader, and many had purchased lamps suited to burning hydrocarbon fuels rather than older models designed for vegetable oils. At that time many rival brands of lamp oil were probably manufactured from coal, surreptitiously using methods that contravened Young's patent. Lignole and other peat oils were not covered by Young's patent, and had the additional advantage of a low flashpoint, unlike the dangerous American petroleum lamp oils that soon took an increasing share of the market.

The next fraction of distillation was semi-solid at normal temperatures as it contained large quantities of solid paraffin wax. These wax flakes (“like flakes of frosted snow”) were filtered off by passing the mixture through filter cloths. The liquid component was cooled (one of the advantages of a cold climate) and filtered again. The separated paraffin wax was, following chemical washes and extraction of residual oil in a hydraulic filter press, dispatched to the major candle works in the London area. The liquid oil was blended with natural fatty oils to produce a light lubricant suitable for oiling the spindles of weaving frames and other light machinery. The tarry residues of distillation were processed to form grease, or sold as a tarry paint said to prevent the fouling of ship's hulls or prevent corrosion of metals.

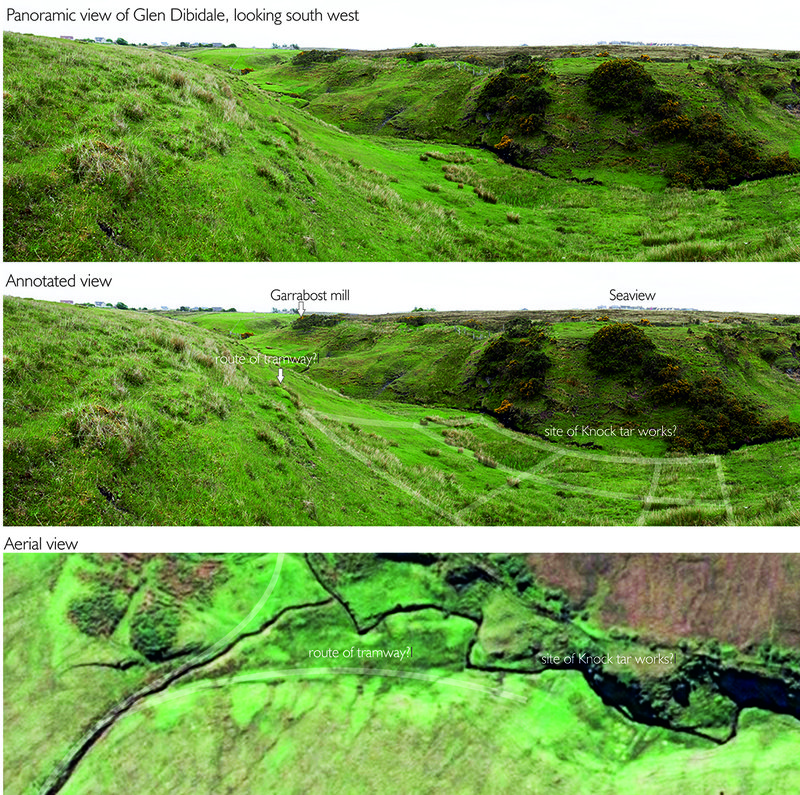

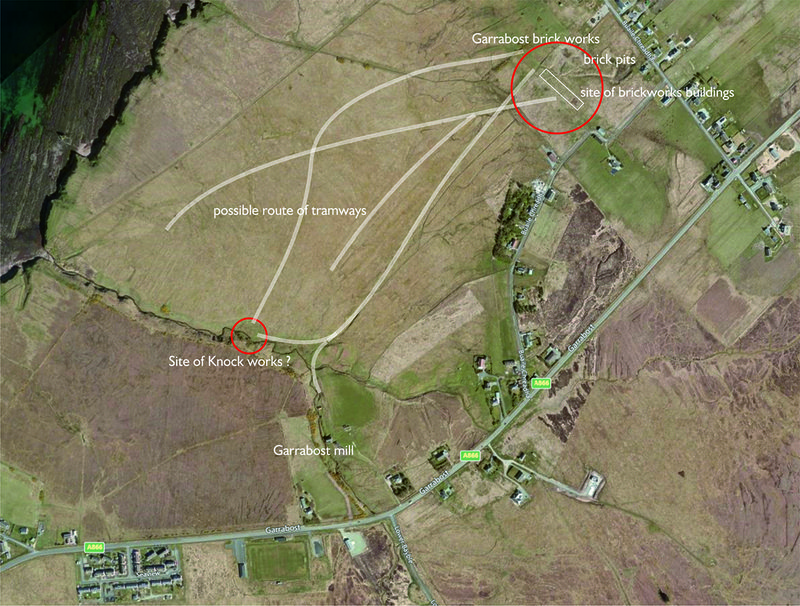

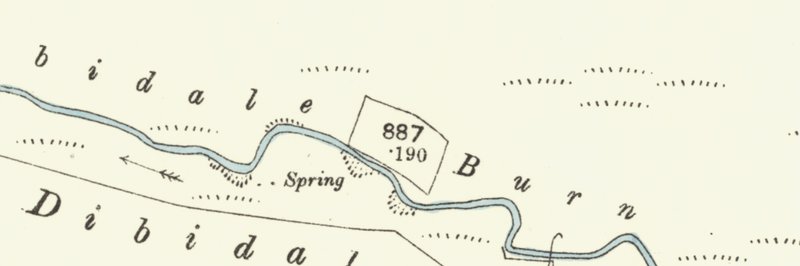

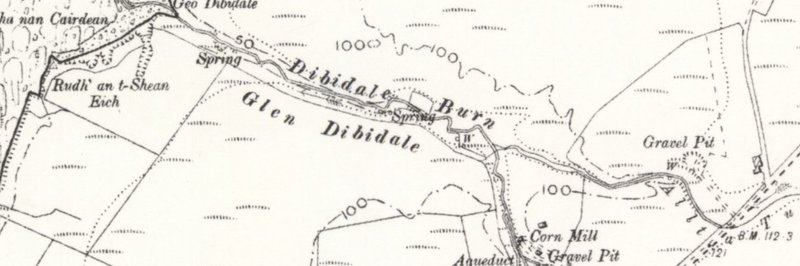

In about 1861, a new plant was built about half a mile south west of Garaboost brickworks in the direction of Cnoc (Knock). According to Ali Whiteford (in his highly recommended history of the oil works “An Enormous Economic Blunder”), the Knock plant was built in Glen Dibidale where the waters of the burn could be used in the washing and processing of tars. A tramway was laid across the moorland to transport tar from Garaboost to Knock and return the products for further processing.

Today, the clay pits of Garaboost are still clearly apparent, even beneath luxuriant growth of moss and grass, and outlines of the main brickworks buildings are evident on aerial images. A long brick building, marked on the 1899 map as a “post office” survives as a storage shed and is said to have once formed part of the brickworks. Certainly the 1852 Ordnance Survey map shows a building on this site.

Between Garaboost and the Glen Dibidale there are traces of various routes across the moorland that might have once been tramways, which lead to cuttings and embankments within the glen. At the end of two of these routes survive various earthworks that might mark the foundations of industrial buildings on a rare area of flat ground beside the burn and extending up the steep valley sides. This seems the most likely location for the Knock tar processing works.

Ali Whiteford's book also suggests that recent drainage works running along the course of the tramway leading down into the glen has revealed the sleepers of the tramway perfectly intact after being buried for a century and a half . This would have been a wonderful and important discovery, but unfortunately not one clearly supported by critical examination of the evidence.

25" OS map c.1895 courtesy National Library of Scotland, with presumed site of Knock tar works in the centre.

Aerial view of presumed site of Knock tar works, perhaps with outline of walls remaining visible.

5" OS map c.1895 courtesy National Library of Scotland

1" OS map c.1895 courtesy National Library of Scotland

Recent images

9th June 2019 - Possible site of Knock tar works

9th June 2019 - Possible site of Knock tar works

9th June 2019 - A section of rail at Garrabost mill; but is it a relic of the original tramway?

9th June 2019 - Length of iron or steel near Garrabost mill. Perhaps a very eroded tramway rail?

9th June 2019 - The glen, looking south to Garrabost mill, with tramway embankment ?

9th June 2019 - Route of tramway, heading down the glen towards possible site of Knock works.

9th June 2019 - Squared timbers and broken clay tiles

9th June 2019 - The timbers give every appearance of being fairly modern fence posts, perhaps inserted into the drainage ditch to control erosion?

9th June 2019 - It has been suggested that the timbers exposed in this drainage ditch are in-situ sleepers of an 1860's tramway, however the large spaces between them, their irregular alignment, their square section, and the absence of screw holes or dog spikes all seem to suggest otherwise.

9th June 2019 - Route of a tramway, looking west from Garrabost..

9th June 2019 - The Red Building at Garrabost, thought to have been part of the complex of buildings at Garrabost brickworks

9th June 2019 - Site of the main group of brickworks buildings at Garrabost, with the Red Building on the skyline to the right.

9th June 2019 - The Red Building, looking towards the hills of Lewis